Coronary artery disease (CAD) is a leading cause of mortality and morbidity globally and its burden is expected to increase due to the rising prevalence of risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidaemia. In conjunction with the 23rd ASEAN Federation of Cardiology Congress held in Bangkok, Thailand, Menarini organized a lunch symposium and product theatre to discuss the significance of optimal medical therapy (OMT) in the management of stable CAD, with a focus on the role of ranolazine (Ranexa®). The symposium featured esteemed speakers Dr Choo Gim Hooi, Consultant Cardiologist from Cardiac Vascular Sentral, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia and Assistant Professor Pattarapong Makarawate from the Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand. At the product theatre, Dr Krisada Sastravaha from Bhumibol Adulyadej Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand presented cases illustrating the new paradigm in the treatment of stable CAD. Both events were chaired by Associate Professor Wiwun Tungsubutra from Siriraj Hospital Faculty of Medicine, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand.

Changing landscape in stable CAD management

“The term ‘stable CAD’ gives the misleading impression that patients are ‘well and stable’. In reality, patients with stable CAD are still at risk of CV events,” said Choo. Quoting data from the REACH (Reduction of Atherothrombosis for Continued Health) registry in stable CAD outpatients (n=38,602), he said, “Approximately 3 of 20 patients with established CAD had a major event or had to be hospitalized within a year of follow-up.” [

JAMA 2007;297:1197-1206]

Importantly, many episodes of ischaemia are asymptomatic, and angina symptoms occur late in the cascade of events that characterize ischaemia. Half of patients with angina also experience silent episodes of ischaemia. [

Circulation 2003;108:1263-1277] Among patients with stable CAD, the presence of angina confers a threefold increase in the risk of CV events. [

Arch Intern Med 2008;168:1423-1428] “Despite this, physicians often underestimate the extent of angina and its impact on patients’ quality of life,” noted Choo. The Coronary Artery Disease in General Practice (CADENCE) study showed that a group of physicians considered their patients’ angina to be optimally controlled even when 48 percent of them have weekly angina. [

Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1491-1499]

“Today, there are more tools for diagnosing CAD. In addition to the conventional noninvasive functional tests (eg, stress electrocardiogram [ECG] tests, nuclear perfusion imaging) and the definitive invasive anatomical tests (eg, coronary catheter angiography), we were able to perform noninvasive anatomical tests (eg, coronary computerized tomography angiography [CCTA]) as well as invasive functional tests (eg, fractional flow reserve assessment),” said Choo. “In particular, CCTA is useful to detect nonobstructive CAD, which would have been missed with conventional noninvasive functional tests. This may be important as data indicate that extensive, multisegmental nonobstructive CAD has similar risk of CV death or (myocardial infarction [MI]) as obstructive CAD.” [

Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2014;7:282-291]

Stable CAD: Revascularization versus medical therapy

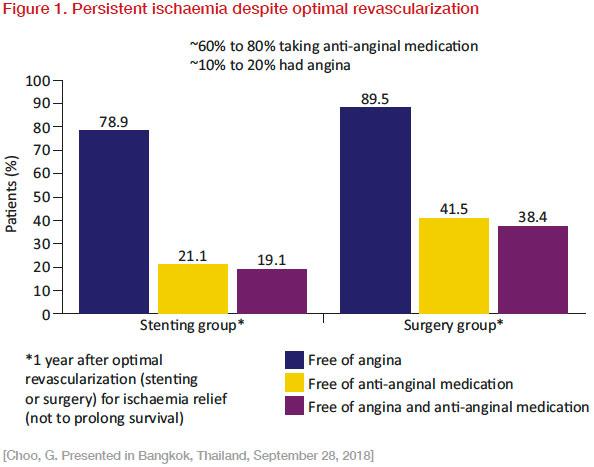

“Revascularization strategies are effective to improve prognosis, symptoms, and best outcomes when guided by the presence of significant ischaemia. However, there are unmet needs in angina and stable CAD management, because there are patients with persistent or recurrent ischaemia or with nonrevascularizable disease (eg, diffuse small vessel disease),” said Choo. He cited data from the Arterial Revascularization Therapies Study (ARTS) which showed persistent angina despite optimal revascularization. In ARTS, approximately 60–80 percent of patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) for treatment of ischaemia (stable or unstable, symptomatic or asymptomatic) were still taking anginal medications 1 year later (

Figure 1). [

N Engl J Med 2001;344:1117-1124]

Similarly, the Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation (COURAGE) trial indicated that PCI added to OMT did not reduce the primary composite endpoints of death and nonfatal MI, or reduce major cardiovascular events, as compared with OMT alone during follow-up. [

N Engl J Med 2007;356:1503-1516]

OMT for stable CAD in the guidelines

Owing to the failings and lack of durability of current revascularization strategies and the number of patients with nonrevascularizable disease, OMT remains the backbone of management for stable CAD, and is sometimes the only available option.

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines recommend a tiered first-choice and a second-choice approach, with short-acting nitrates, beta (β)-blockers, or calcium channel blockers (CCBs) as first-line therapies, and ivabradine, long-acting nitrates, nicorandil, ranolazine, and trimetazidine as second-line therapies. [

Eur Heart J 2013;34(38):2949-3003]

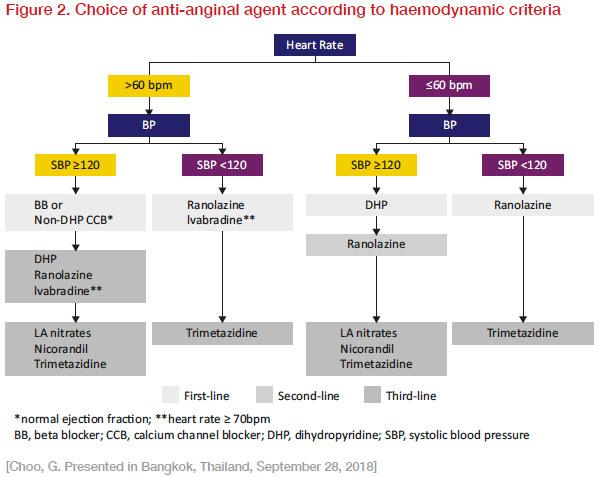

“However, this recommendation is based more on prescribing tradition and expert opinion rather than evidence. Newer anti-anginal drugs, which are classified as second choice, actually have more robust and contemporary clinical data to support their use than the traditional first-choice drugs,” said Choo. “The selection and combination of anti-ischaemic agents should be based on patients’ haemodynamic status, comorbidities, and mechanisms of angina (

Figure 2).” [

Int J Cardiol 2016;220:445-453]

Ranolazine: Innovative agent in the real-world management of stable CAD

Despite the use of traditional anti-anginal agents (β-blockers, CCBs, and nitrates), patients still report an average of two angina attacks per week, said Makarawate. “A significant percentage of patients have relative intolerance to full doses of traditional first-line agents due to the haemodynamic effects on blood pressure (BP), heart rate, and/or atrioventricular nodal conduction. Thus, there is a need for newer anti-anginal drugs such as ranolazine. Ranolazine is a suitable option for patients who are intolerant to, or inadequately controlled by, first-line agents.”

“Ranolazine, the first-in-class late cardiac sodium current inhibitor, has been studied in four key randomized, placebo-controlled trials on stable CAD patients with chest pain on exertion for more than 3 months,” explained Makarawate. “The studies investigated ranolazine as monotherapy (crossover with standard treatment; MARISA), in combination with standard treatment in a parallel study (CARISA), in combination with amlodipine 10 mg in a parallel study (ERICA), and in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) as an add-on to two standard anti-anginal agents (TERISA). Results showed that ranolazine increased exercise duration, time to angina and time to 1-mm ST-depression (MARISA, CARISA, TERISA), and decreased angina frequency and nitroglycerin use (CARISA, ERICA).”

Importantly, the anti-anginal and anti-ischaemic activity of ranolazine occurs without affecting heart rate or BP to a clinically significant extent. [

Drugs 2008;68:2483-2503] Ranolazine significantly reduces ischaemia by improving regional coronary blood flow in areas of myocardial ischaemia. [

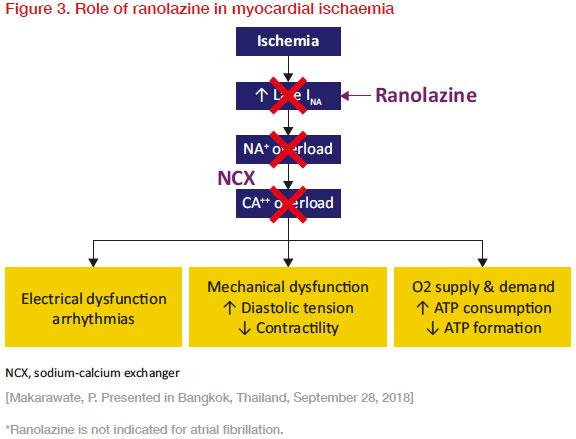

J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:934-942] Ranolazine inhibits late sodium current (I

Na), thus preventing sodium overload of the cell, which consequently prevents reverse mode sodium–calcium exchange and diastolic accumulation of calcium. Consequently, oxygen demand is decreased by relieving diastolic tension, and oxygen supply is increased by improving diastolic flow (

Figure 3). [

Clin Res Cardiol 2008;97:222-226]

Moreover, ranolazine has effects beyond anti-angina. It has also been shown to improve diabetic control by reducing HbA

1c, and has anti-arrhythmic properties, reducing supraventricular and ventricular tachyarrhythmias, as well as a trend of reducing atrial fibrillation*, said Makarawate.

Case studies and clinical experience with Ranexa®

Makarawate detailed a case of a 68-year-old male who presented with chest pain during walking (Canadian Cardiovascular Society [CCS] III, New York Heart Classification I). “The patient had a history of hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidaemia, and a history of old [MI] status post PCI for 1 year with nonsignificant stenosis in the left circumflex artery and right coronary artery (RCA). His BP was 140/90 mm Hg, pulse 64 bpm, and his physical exam was unremarkable except for point of maximal impulse (PMI) at 6th intercostal space (ICS) with pansystolic murmur (PSM) III at apex. He was on metformin 500 mg thrice daily, aspirin 81 mg once daily, bisoprolol 2.5 mg once daily, atorvastatin 40 mg at night, and enalapril 20 mg once daily. Chest x-ray for PMI revealed a dilated 6th ICS. An echocardiogram showed that the left atrium (LA) and left ventricle (LV) were dilated; there was reduced LV systolic function with thinning of the anterior wall and LV dyssynchrony (ejection fraction [EF]=38 percent). This patient was classified as intermediate risk.”

“According to the ESC guidelines, patients with intermediate risk should try [OMT] and consider invasive coronary angiography, depending on comorbidities and patient preferences. We decided to optimize the patient’s medical therapy by adding furosemide 20 mg, amlodipine 5 mg, and isordil 10 mg to his daily medication regimen, and increasing the dose of bisoprolol from 2.5 mg to 5 mg. Despite this, the patient still had some chest pain on exertion,” Makarawate elaborated.

“As the patient’s heart rate was quite low at around 60 bpm, it was not desirable to titrate the β-blocker and add ivabradine. It was decided to start ranolazine 500 mg twice daily, as the patient had normal corrected QT interval and no significant drug interactions to ranolazine. Furthermore, ranolazine had demonstrated efficacy in patients with diabetes, and has possible benefits to HbA

1c and future cardiac arrhythmia. Upon follow-up, the patient reported resolution of the chest pain,” recounted Makarawate.

At the product theatre, Sastravaha discussed the application of the new paradigm in the treatment of stable CAD with the following two cases:

Case 1

A 67-year-old female with a history of hypertension and hyperlipidaemia presented with progressively worsening chest pain on exertion (CCS II). Her current medications included amlodipine 5 mg once daily and simvastatin 20 mg once daily. Her BP was 132/82 mm Hg, heart rate was 75 bpm, and body mass index (BMI) was 25.1 kg/m

2; physical examination and ECG were unremarkable. Laboratory findings showed an elevated fasting blood glucose of 102 mg/dL, an LDL of 108 mg/dL, and HDL-C of 45 mg/dL. The hs-Troponin T (cTnT, <0.01 ng/mL), eGFR, and TSH were within normal range. An echocardiogram showed normal overall LV function and normal valvular function. She was diagnosed with angina pectoris. Her medication regimen was changed to bisoprolol 5 mg, aspirin 81 mg, atorvastatin 40 mg, and amlodipine 5 mg. She returned 3 weeks later with improved BP (128/72 mm Hg) and heart rate of 64 bpm, but still had angina CCS II. Myocardial perfusion scintigraphy detected an inferior wall defect and EF of 60 percent.

The patient was sent for coronary angiography, which showed total occlusion in the mid RCA. Given that her LV function was normal, and an arteriovenous fistula was present, she was not suitable for immediate PCI, and intensive medical management was prescribed for symptom relief. Ranolazine 500 mg twice daily was added to her regimen. After a month, she reported symptom relief and did not experience any adverse effects.

Case 2

A 56-year-old male, former smoker, with T2D who underwent CABG 2 years prior to his visit presented with recurrent progressive angina (CCS III). His medications included aspirin 81 mg once daily, enalapril 10 mg twice daily, bisoprolol 5 mg once daily, amlodipine 5 mg once daily, atorvastatin 40 mg once daily, ezetimibe 10 mg once daily, omeprazole 20 mg once daily, and metformin 1 g twice daily. His BP was 118/72 mm Hg, heart rate was 64 bpm, and BMI was 26.3 kg/m

2. His physical examination was unremarkable except for PMI at 6th ICS 1” lateral to midclavicular line, LV S4 gallop, and PSM grade II/VI at apex. Laboratory tests showed a fasting blood glucose of 154 mg/dL, normal eGFR (72 mL/min/1.73 m

2), negative cTnT (<0.01 ng/mL), LDL of 67 mg/dL and HDL-C of 42 mg/dL. The echocardiogram showed mild LA and LV dilatation, EF of 50 percent, global hypokinesis with anterior and apical segments affected more severely, and grade 2+ mitral regurgitation. Following coronary angiography, he was diagnosed with ischaemic cardiomyopathy with mild LV dysfunction status post CABG and diffuse distal disease. As there was significant ostial vein graft stenosis, a PCI at ostial saphenous vein graft to obtuse marginal artery was performed. Trimetazidine MR 35 mg twice daily was added. Unfortunately, the angina still persisted. Trimetazidine was substituted with ranolazine 500 mg twice daily and subsequently increased to 750 mg twice daily. The patient’s symptoms were relieved.

“As CABG, which improves patient survival, had already been performed on this patient, the main goal of management is symptom relief. Various medications for angina management were tried, and ranolazine was shown to effectively relieve symptoms in this case,” said Sastravaha.

Key takeaways

Revascularization strategies, such as PCI or CABG, are effective to improve prognosis, symptoms, and clinical outcomes when guided by the presence of significant ischaemia. However, data from ARTS and COURAGE demonstrated that angina may persist or recur despite optimal revascularization. Moreover, a significant proportion of patients have nonrevascularizable disease. Therefore, for most patients with stable CAD, OMT should remain the cornerstone of therapeutic approach.

The ESC and American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association recommend ranolazine as a second-line therapy for the management of angina. Multiple, randomized, placebo-controlled trials have confirmed its benefit in patients with stable CAD, improving functional capacity and decreasing anginal episodes. Its unique mechanism of action enables it to provide ischaemic relief without affecting BP and heart rate, making it a highly suitable alternative for patients who are intolerant to the full doses of traditional anti-anginal medication (β-blockers, CCBs, and nitrates) owing to its haemodynamic effects, or when traditional agents fail to provide adequate control of symptoms.

![[PD Test]]Real-world management of stable coronary artery disease](https://sitmspst.blob.core.windows.net/images/articles/real-world-management-of-stable-coronary-artery-disease-93ab5b84-82de-4759-b216-a18ce413727b-thumbnail.jpg)