History and presentation

A 66-year-old male nonsmoker and nondrinker complained of generalized bone pain, poor appetite and abdominal discomfort in December 2022. He had hypertension, which was controlled with amlodipine/valsartan 5 mg/80 mg, and sleep apnoea. He was also a hepatitis B virus (HBV) carrier on maintenance entecavir. He had no family history of prostate cancer.

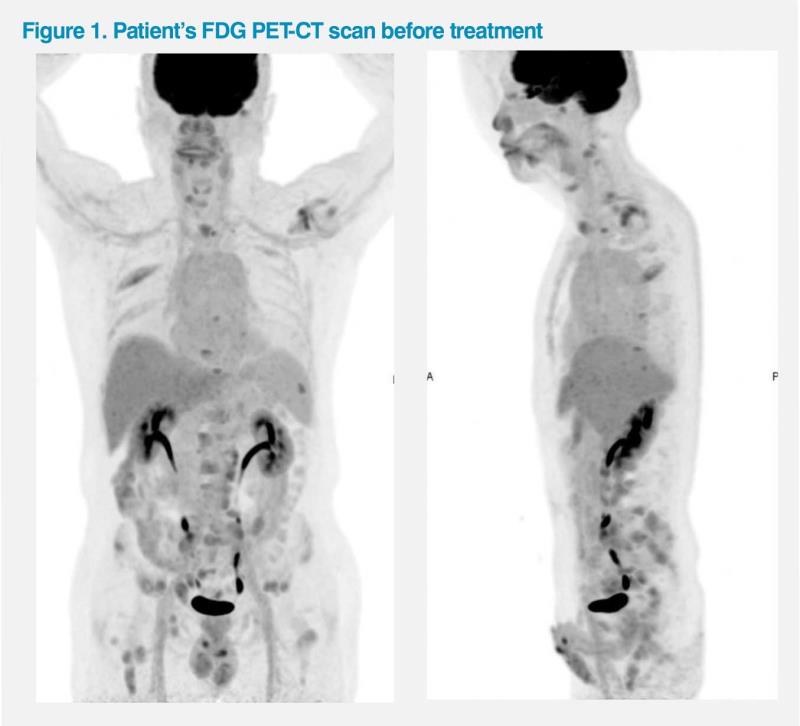

The patient initially sought consultation at another clinic and was assessed to have an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) of 1, since he was unable to work due to his symptoms. A fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET-CT scan revealed multiple metastatic lesions in the bones as well as in the abdominal, pelvic and mediastinal lymph nodes (LNs). (Figure 1) His prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level was elevated at 717 ng/mL. A biopsy of the pelvic LN revealed high-grade adenocarcinoma. Further tests led to the diagnosis of metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC; Gleason score not reported).

Treatments and response

In January 2023, the patient started androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) with monthly subcutaneous injections of the luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone antagonist, degarelix (240 mg loading dose, administered as two separate injections of 120 mg, then 80 mg QM). He gradually regained appetite and had less bone pain. After 1 month, his PSA level decreased to 432 ng/mL. However, his ECOG PS remained at 1 due to fatigability.

In February 2023, he sought consultation at our clinic. After further investigations, he was assessed to have high-risk metastatic prostate cancer based on the markedly elevated baseline PSA level as well as high-volume disease with presence of bony and distant LN metastases.1 He had no actionable mutations (ie, negative for BRCA1/2 mutations). Since he was relatively fit, chemotherapy plus an androgen receptor inhibitor (ARI) was recommended.1 However, the patient only agreed to add an oral ARI, darolutamide, at 600 mg BID, to ongoing ADT with degarelix.

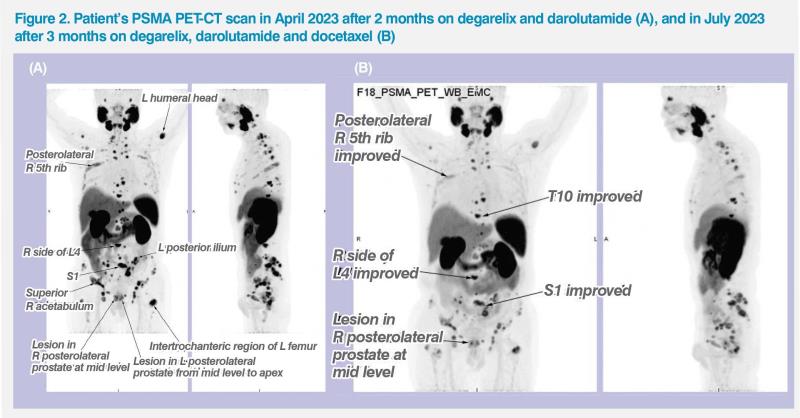

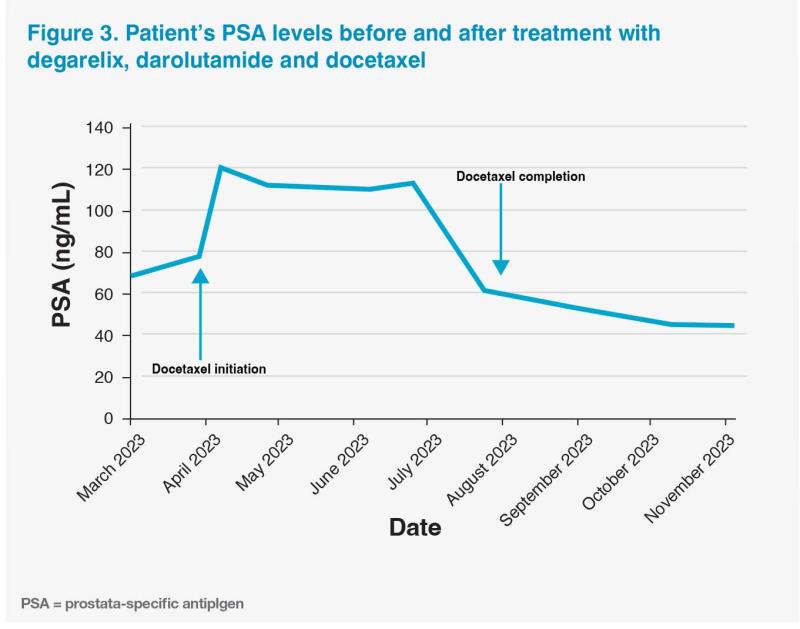

The patient experienced no side effects while on degarelix and darolutamide. He also did not require any dose adjustments despite concurrently receiving antihypertensive and anti-HBV medications. Although his symptoms gradually improved (eg, less fatigability), his PSA level plateaued at around 70 ng/mL (ie, 72 ng/mL in March 2023; 68 ng/mL in April 2023). To improve imaging sensitivity, the patient underwent a prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) PET-CT scan in April 2023, which showed substantial PSMA uptake in multiple bone regions, LNs and the prostate gland.2 (Figure 2A)

The patient agreed to start chemotherapy with docetaxel (IV infusions at 75 mg/m2 Q3W) in April 2023. He also received granulocyte colony–stimulating factor (GCSF) prophylaxis to reduce his risk of developing neutropenia.

A week after starting docetaxel, the patient experienced a PSA flare, with his PSA level increasing to 120 ng/mL, followed by a gradual decline observed during subsequent regular monitoring.3 (Figure 3) He also experienced several adverse events (AEs) while on docetaxel treatment (eg, grade 4 alopecia and grade 1 fatigue, anorexia, arthralgia, and peripheral neuropathy), which were transient (ie, approximately 2 weeks’ duration at most) and managed conservatively. He was able to continue with the triplet regimen without any dose reductions or treatment interruptions.

PSMA PET-CT scan in July 2023 showed good response to triplet therapy, with markedly reduced PSMA uptake in the bones, LNs and prostate as well as resolution of PSMA uptake in other previously positive areas. (Figure 2B) He completed six cycles of docetaxel in August 2023, and his latest PSA level was 53 ng/mL in September 2023. Docetaxel-related AEs had mostly resolved, with his hair gradually growing back.

The patient is currently well and has returned to work (ECOG PS, 0). He remains on degarelix and darolutamide, and will continue with this regimen until disease progression or treatment intolerance.

Discussion

Although our patient initially started treatment with ADT alone, current guidelines reserve this option only for patients with definite contraindications to treatment intensification. Systemic therapy for mHSPC requires at least a doublet regimen with ADT plus an androgen-receptor pathway inhibitor or docetaxel.1,4 Latest National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines strongly encourage triplet therapy for patients with high-volume mHSPC who are fit for chemotherapy, such as our patient.1

The two triplet regimens recommended by the NCCN guidelines for fit patients with high-volume mHSPC include adding either the antiandrogen drug, abiraterone, or the ARI, darolutamide, to ADT plus docetaxel. This recommendation is based on the improved overall survival (OS) data from the phase III clinical trials, PEACE-1 (A Phase III Study for Patients With Metastatic Hormone-Naïve Prostate Cancer) for abiraterone and ARASENS (ODM-201 in Addition to Standard ADT and Docetaxel in Metastatic Castration Sensitive Prostate Cancer) for darolutamide. 1,5-7

Although PEACE-1 reported longer OS among patients who received abiraterone vs those who did not (hazard ratio [HR], 0.82; 95.1 percent confidence interval [CI], 0.69–0.98; p=0.030), the trial had a 2 x 2 factorial design where patients with mHSPC received either standard of care (SoC; mostly ADT plus docetaxel), SoC plus abiraterone, SoC plus radiotherapy, or SoC plus abiraterone plus radiotherapy.5,6 On the other hand, the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled ARASENS study is currently the only trial of triplet therapy in patients with mHSPC that was designed and powered to evaluate survival benefit of an ARI specifically added to a docetaxel-containing regimen. It compared the OS of patients with mHSPC who received a combination of darolutamide (600 mg BID), ADT and docetaxel vs placebo, ADT and docetaxel.7

The primary analysis of ARASENS included 1,306 patients (651 in the darolutamide group and 655 in the placebo group). Patients receiving darolutamide had longer duration of treatment vs those receiving placebo in both high-volume disease (32.9 months vs 15.3 months) and low-volume disease (43.6 months vs 26.5 months) subgroups. Results showed that the risk of death was 32.5 percent lower in the darolutamide vs placebo group (HR, 0.68; 95 percent CI, 0.57– 0.80; p<0.001). OS rate at 4 years was 62.7 percent in the darolutamide group vs 50.4 percent in the placebo group, clearly showing that OS was significantly longer among patients who received darolutamide.7

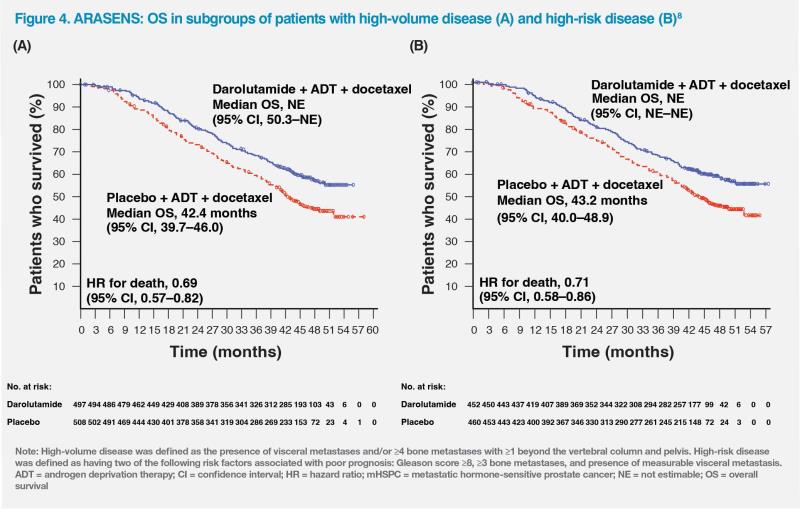

The survival benefits associated with darolutamide were also consistently demonstrated across different prespecified subgroups, namely, patients with high-volume disease (n=1,005; HR, 0.69; 95 percent CI, 0.57–0.82), high-risk disease (n=912; HR, 0.71; 95 percent CI, 0.58–0.86), and low-risk disease (n=393; HR, 0.62; 95 percent CI, 0.42–0.90). (Figure 4) In the low-volume disease subgroup, results were suggestive of a trend of improved survival with darolutamide (HR, 0.68; 95 percent CI, 0.41–1.13), but the relatively small sample size (n=300) may have contributed to the 95 percent CI crossing 1.0.8

Achieving a longer time to progression to castration-resistant disease is an important treatment endpoint because metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) is a more advanced disease with less favourable survival outcomes.9 In ARASENS, adding darolutamide to ADT and docetaxel resulted in significantly longer time to mCRPC vs placebo (HR for disease progression, 0.36; 95 percent CI, 0.30–0.42; p=0.01), implying that those whose cancer remains hormone-sensitive for longer are likely to attain longer OS.7,9

Although survival outcomes are crucial efficacy endpoints in clinical trials, symptomatic relief is especially important for preserving or improving patients’ quality of life.10,11 In ARASENS, time to pain progression (HR, 0.79; 95 percent CI, 0.66–0.95; p=0.01), as well as symptomatic skeletal event–free survival (HR, 0.61; 95 percent CI, 0.52–0.72; p<0.001) and time to first symptomatic skeletal event (HR, 0.71; 95 percent CI, 0.54–0.94; p=0.02) were significantly longer in the darolutamide vs placebo group.7

Importantly, use of darolutamide was not associated with a higher rate of AEs vs ADT plus docetaxel, with the incidence of AEs being similar in both groups (eg, overall frequency of grade 3/4 AEs was 66.1 percent vs 63.5 percent in the darolutamide vs placebo group). The most common AEs of all grades (reported in ≥25 percent of patients, namely, alopecia, neutropenia, fatigue, anaemia, peripheral oedema, arthralgia, and diarrhoea) predominantly occurred during the overlapping docetaxel treatment period in both groups, consistent with our patient’s experience.7 PSA flares, characterized by an early rise followed by a decline of PSA level, have been observed in patients with prostate cancer after initiating treatment with docetaxel, including our patient, but are not known to influence disease-specific outcomes.12

Use of abiraterone as the ARI component of triplet therapy for mHSPC has been associated with an increased incidence of hypertension in the PEACE-1 trial. Since our patient had hypertension, darolutamide was a more appropriate option than abiraterone.6 Darolutamide is also a structurally distinct ARI with low blood-brain barrier penetration, which may translate to fewer central nervous system (CNS) side effects, potentially making it more appropriate than abiraterone for elderly patients, especially those with CNS conditions (eg, dementia, psychosis, psychological disorders, past history of seizures).7,13 Darolutamide has limited potential for clinically relevant drug-drug interactions, which is an advantage in patients receiving other medications, such as our patient.7 Unlike abiraterone, darolutamide does not require concurrent use of steroids, making it a more convenient and better tolerated option for many patients.1,13

Based on our clinical experience, fatigue is a common AE associated with darolutamide, but it is usually manageable and mild. Some patients have also reported darolutamide-associated skin rash while on treatment, but it tends to be mild and less notable than in patients treated with another ARI, apalutamide.13,14

In summary, the combination of darolutamide, ADT and docetaxel has demonstrated favourable tolerability and positive survival outcomes in the phase III ARASENS trial, leading to this regimen becoming the SoC in chemotherapy-eligible patients with high-volume and high-risk mHSPC, making it a suitable choice for our patient.7,8 (Figure 4)