Presentation and history

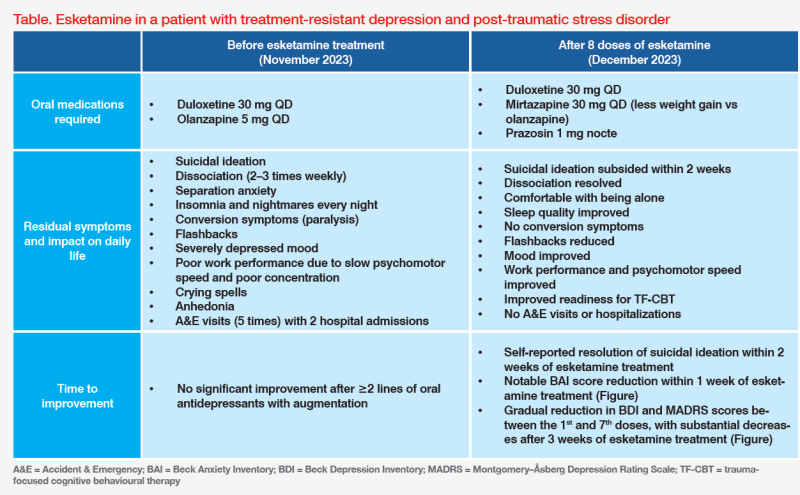

This is the case of a young female professional who was sexually assaulted by her older brother when she was in primary school. The patient had not developed diagnosable psychiatric disorders until April 2023, when exposure of the childhood traumatic event triggered moderate depression (Beck Depression Inventory [BDI] score, 20) and mild anxiety (Beck Anxiety Inventory [BAI] score, 12) as well as severe post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) with full-blown symptoms, including flashbacks, insomnia and nightmares every night, anhedonia, dissociation (2–3 times weekly) and conversion symptoms (paralysis) on her right hand and left leg. She withdrew not only from the perpetrator, but also from other family members. She had crying spells, separation anxiety with friends, and decreased work performance due to slow psychomotor speed and poor concentration. (Table)

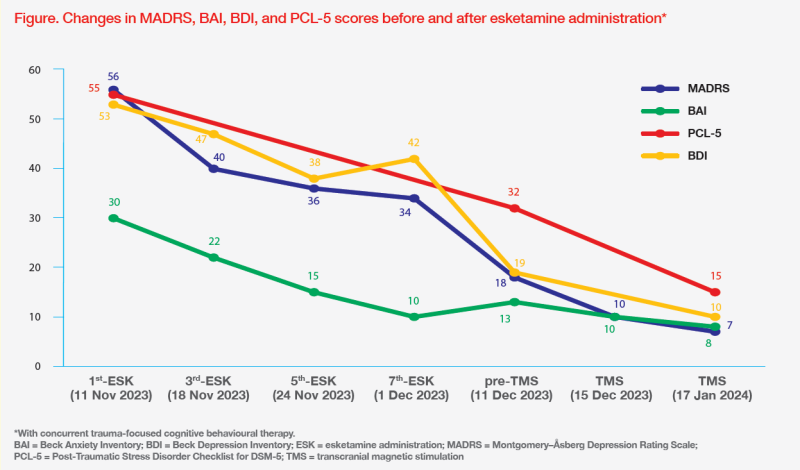

The patient initially received oral antidepressants (sertraline 50 mg QD in August 2023; switched to duloxetine 30 mg QD in September 2023) followed by antipsychotic augmentation (brexpiprazole 1 mg QD in October 2023; switched to olanzapine 5 mg QD in November 2023). Despite oral medication adjustments, her Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) score increased to 56, with a BDI score of 53 and a PTSD Checklist 5 (PCL-5) score of 55, indicating treatment-resistant depression (TRD) and severe PTSD. (Figure)

As a result of multiple suicide attempts and conversion symptoms, the patient was sent to the Accident & Emergency (A&E) department five times and hospitalized twice. Given her severe psychiatric symptoms and suicidality, esketamine nasal spray was initiated.

Treatment with esketamine nasal spray and response

On 11 November 2023, the patient started her first dose of intranasal esketamine at our clinic. After dosing, she was monitored closely by our nurses for 2 hours in a private room with the company of her friends. Right after esketamine administration, she had dissociative reactions with loud screaming of “I am scared” and “Don’t come close to me”, but the reactions subsided within 45 minutes. She also received concurrent trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy (TF-CBT) the next day following each esketamine dose.

As the patient had dissociative reactions after the first two doses of esketamine, premedication with alprazolam 0.5 mg was given 15 minutes beforehand from the 3rd dose to the 6th dose. Since then, the dissociative reactions substantially reduced, and sleep quality improved. Notably, no dissociation occurred in any TF-CBT sessions or after the final dose of esketamine, even without premedication.

The patient tolerated esketamine well. Slight blood pressure (BP) elevations of 10–30 mm Hg, which resolved within 1 hour, were observed from the 4th to 8th dose, but not with the first few doses, despite the dissociative reactions. No other side effects were reported during and between esketamine administrations, although weight gain (+5 kg) occurred with olanzapine.

The patient responded well to esketamine and TF-CBT, with rapid resolution of suicidal ideation within 2 weeks and gradual reduction in BDI, MADRS and BAI scores. (Figure) As such, olanzapine was switched to a ‘milder’ antipsychotic with less weight gain potential (mirtazapine 15 mg QD) in November 2023. On 28 November 2023, prazosin 1 mg nocte was added to reduce nightmares.1 (Table)

Towards the end of esketamine treatment, the patient’s energy level increased, and psychomotor speed improved. Her anxiety symptoms also improved, and flashbacks significantly decreased. Her work performance improved and she felt comfortable without her friends' presence. (Table) Before her last dose of esketamine on 5 December 2023, there were substantial reductions of both BDI (from 42 to 19) and MADRS (from 34 to 18) scores. (Figure)

After eight doses of esketamine and concurrent TF-CBT, the patient’s PCL-5 score also decreased substantially to 32, which, however, is still considered high. (Figure) Therefore, she started repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) three times weekly for residual PTSD symptoms.

As of 17 January 2024, the patient had completed 15 sessions of TMS. Her BDI, MADRS and BAI scores were 10, 7 and 8, respectively, and PCL-5 score further decreased to 15. (Figure) She had not visited the A&E or been hospitalized since starting esketamine treatment. (Table)

Discussion

Comorbid TRD-PTSD is associated with more severe clinical presentation and reduced treatment efficacy than either disorder alone.2 Our patient with mild anxiety, severe TRD and severe PTSD did not respond to ≥2 lines of oral antidepressant treatment, as her psychiatric symptoms, including suicidality, worsened, resulting in five A&E visits and two hospitalizations in 7 months. Since this case was judged as a psychiatric emergency, esketamine was indicated as an acute intervention, as supported by results of two pivotal phase III studies, ASPIRE I and ASPIRE II.3

Pooled data from ASPIRE I (n=226) and ASPIRE II (n=230) showed that esketamine plus standard of care significantly reduced depressive symptoms, as measured by MADRS score at 24 hours after the first dose vs placebo (least-square [LS] mean difference, 3.8; 95 percent confidence interval [CI], -5.75 to -1.89), in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) and acute suicidal ideation or behaviour. Rapid effect was observed as early as 4 hours after the first dose (LS mean difference, -3.4; 95 percent CI, -5.05 to -1.71), and the effect was sustained at 25 days (LS mean difference, -3.4; 95 percent CI, -5.36 to -1.36).4

Apart from its rapid effect, esketamine was the drug of choice for our patient because it potentially improves symptoms of both TRD and PTSD. In an open-label, single-arm, retrospective pilot study of 11 patients with TRD-PTSD, mean MADRS scores significantly decreased from 38.6 to 18.2 (p<0.001) after 6 months of intra-nasal esketamine. Rapid improvement in suicidality was also observed, with the proportion of moderately to severely suicidal patients decreasing from 63.6 percent at baseline to 27.3 percent after 1 month of treatment.5 Furthermore, an open-label retrospective analysis of 35 military veterans with comorbid depression and PTSD showed significant reductions in depressive (absolute change in Patient Health Questionnaire-9 score, -5.1; p<0.05) and PTSD symptoms (absolute change in PCL-5 score, -15.5; p<0.05) after 4 weeks of esketamine treatment.6 Similar responses were seen in our patient who achieved notable reductions of BDI, MADRS and PCL-5 scores. (Figure)

Commencing esketamine treatment was life-changing for our patient, who experienced rapid resolution of suicidal ideation and no A&E visits or hospitalization since starting treatment. Other TRD-PTSD symptoms, including dissociation, separation anxiety, flashbacks, mood symptoms, insomnia, and nightmares, significantly improved after 4 weeks of esketamine. Notably, her early clinical response was not adequately reflected in the BDI and MADRS score decline before the 7th dose (response defined as ≥50 percent decrease from baseline).7 Clinicians should be aware that esketamine’s anti-depressant effect, especially in patients with ≥1 psychiatric disorder, can be delayed, and treatment should not be stopped too early.

In both MDD and PTSD, patients are more sensitive to negative emotional stimuli which trigger an increased activation of brain regions involved in fear and stress responses, such as amygdala and prefrontal cortex. Glutamate is the main excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain and plays a crucial role in stress responsivity and the formation of traumatic memories. It is postulated that esketamine, the S enantiomer of ketamine, modulates glutamate neurotransmission, which may help restore normal functioning through N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor blockage in these brain regions and alleviate symptoms of PTSD and MDD.3,5

Our case illustrates that esketamine can potentiate TF-CBT and the two treatment modalities can be applied in parallel, which may be due to ketamine’s mechanism of action in facilitating neuroplasticity involved in new memory formation, fear extinction, and restructuring of traumatic memories. Combining ketamine with psychotherapy may facilitate emotional learning through enhanced neuroplasticity, reductions in defensiveness, and enhanced treatment adherence and engagement.5,8 Our esketamine-treated patient, for example, felt more comfortable and found it easier to share thoughts and feelings during TF-CBT sessions. (Table)

Dissociative effects are common with intranasal esketamine. However, as illustrated in our patient, pre-existing dissociation is not a contraindication to esketamine treatment. Interestingly, esketamine’s dissociative effects may promote better treatment outcomes by allowing patients to verbalize their traumatic experience and create new positive associations.5 In cases where esketamine-associated dissociation is excessive or disturbing to patients, it can be managed by premedication with benzodiazepines, such as alprazolam, shortly before drug administration.9 Transient BP elevation is also common with esketamine, but it is often self-limiting, as observed in our patient. Some patients may experience dysgeusia, which can be alleviated by breathing through the mouth.9,10