Presentation and investigation

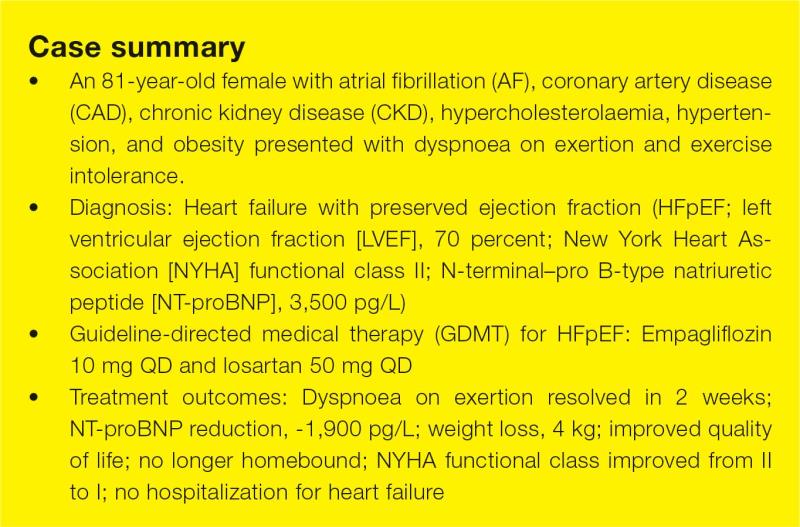

An 81-year-old homebound, obese (BMI, 31 kg/m2) female complained of dyspnoea on exertion and exercise intolerance in 2023. The patient often needed to stop after walking for a distance of two blocks or climbing eight steps of stairs (New York Heart Association [NYHA] functional class II), which limited her daily and social activities.

The patient had multiple comorbidities, including atrial fibrillation (AF) treated with dabigatran 110 mg BID and bisoprolol fumarate 2.5 mg QD, mild coronary artery disease (CAD), stage 3B chronic kidney disease (CKD; estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR], 40 mL/min/1.73 m2), hypercholesterolaemia treated with atorvastatin 20 mg QD, and long-standing hypertension (blood pressure [BP], 124/76 mm Hg) controlled with losartan 50 mg QD.

Physical examination revealed mild lower limb oedema, and bioimpedance analysis showed high total body water content, suggesting fluid retention. Echocardiography showed preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 70 percent and mild LV hypertrophy, but no valvular heart disease. To determine the cause of exertional dyspnoea, Holter monitoring was started in May 2023, which detected no arrhythmia, thus eliminating the possibility of AF-associated dyspnoea. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) was suspected, which was subsequently confirmed by elevated N-terminal–pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) level at 3,500 pg/mL.

Treatment and response

In June 2023, a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor, empagliflozin (10 mg QD), was initiated as guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) for HFpEF, together with losartan 50 mg QD.1,2

After 2 weeks of empagliflozin treatment, the patient’s exertional dyspnoea and lower limb oedema resolved, with improvements observed in NYHA functional class (from II to I) and NT-proBNP level (from 3,500 pg/L to 1,600 pg/L). Her body weight also dropped markedly by 4 kg, which could be due to the diuretic effect of SGLT2 inhibition, as indicated by normalization of total body water content on bioimpedance analysis. The patient’s renal function remained stable, and she had not been hospitalized for HF since diagnosis.

The patient tolerated empagliflozin well without experiencing any adverse effects (AEs). Last seen in December 2023, she was satisfied with the treatment. She reported an improved quality of life (QoL) as she was no longer homebound and experienced no limitations in physical and social activities.

Discussion

HFpEF accounts for over half of all HF cases, yet it remains underdiagnosed due to normal LVEF and nonspecific symptoms including dyspnoea, exercise intolerance, fatigue, and oedema.3 There is a common misconception among patients that these symptoms are a “normal” part of ageing. Furthermore, symptoms of HFpEF often overlap with those of underlying comorbidities (eg, AF, obesity), making a definitive diagnosis more complex.3

In the primary care setting, HFpEF is a potential diagnosis in patients with normal LVEF and ≥1 HF symptom.2 Potential cardiac and noncardiac HF mimics should be identified and addressed one by one. As demonstrated in this patient’s case, suboptimally controlled AF can be ruled out by Holter monitoring.

Clinically, HFpEF patients tend to be old (approximately ≥75 years of age), female (55–73 percent), and present with comorbidities such as overweight or obesity (>80 percent), hypertension (75 percent), AF (40–60 percent), CAD (51 percent), renal disease (25–50 percent), and diabetes (40 percent).3-5 Consistent with the observation in our patient, these characteristics and comorbidities increase the likelihood of HFpEF. In suspected cases, natriuretic peptide test should be conducted, and HFpEF diagnosis can be established if NT-proBNP is >125 pg/mL or BNP is ≥35 pg/mL.2

Treatment options for HFpEF are limited. All previous studies of angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), aldosterone receptor antagonists (MRAs), and angiotensin receptor/neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) failed to meet their primary endpoints. The phase III EMPEROR-Preserved trial of empagliflozin is the first study in HF with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF) and HFpEF to meet its primary endpoint.2,6,7

In EMPEROR-Preserved, 5,988 HF patients with NYHA functional class II–IV and LVEF ≥40 percent were randomized 1:1 to receive empagliflozin (10 mg QD) or placebo, in addition to usual therapy.7

After a median follow-up of 26.2 months, empagliflozin showed a 21 percent relative risk reduction for the composite primary endpoint of cardiovascular (CV) death or hospitalization for heart failure (HHF) vs placebo (hazard ratio [HR], 0.79; 95 percent confidence interval [CI], 0.69–0.90; p<0.001), which was mainly driven by reduction in HHF (HR, 0.71; 95 percent CI, 0.60–0.83). Statistical significance was achieved as early as 18 days following randomization. The beneficial effect of empagliflozin was generally consistent across all prespecified subgroups, including patients with or without diabetes at baseline (HR, 0.79 and 0.78, respectively).7,8

Notably, most HFpEF patients are older with multiple comorbidities and geriatric conditions, such as polypharmacy, cognitive impairment and frailty, which may increase the risk of all-cause death. It is therefore intrinsically challenging for HFpEF medications to reduce all-cause mortality, suggesting that HHF, QoL and functional capacity may be more realistic and appropriate endpoints for HFpEF.9

In a prespecified analysis of EMPEROR-Preserved, empagliflozin significantly improved health status and QoL, as assessed by the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) and subdomains such as symptom frequency and burden, QoL, and social limitation. These improvements were seen early in week 12 and sustained for ≥1 year.10 In our patient, symptomatic relief and QoL improvement were rapid (achieved at week 2) and durable.

Although not experienced by our patient, uncomplicated urinary tract and genital infections were commonly reported AEs (9.9 percent and 1.9 percent, respectively) in EMPEROR-Preserved. Genital hygiene advice should be provided before treatment initiation, particularly for female patients.7,11

In my clinical experience, SGLT2 inhibitors and diuretics should be initiated early in HFpEF patients with fluid retention, while antihypertensive therapy (eg, ARB) should be prioritized in those with high BP. Importantly, the 2023 American College of Cardiology Expert Consensus Decision Pathway suggested that all HFpEF patients should be treated with an SGLT2 inhibitor unless contraindicated (class of recommendation, 2a) to reduce CV death and HHF and improve health status.2