Early diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is important such that treatment can be initiated

early to prevent joint damage. Senior consultant Dr Faith Chia Li-Ann

and senior resident Dr Paula P Tjokrosaputro from the Department of

Rheumatology, Allergy and Immunology in Tan Tock Seng Hospital (TTSH),

Singapore share their insights with Pearl Toh on the role of GPs in

caring for patients with RA in the primary care setting.

RA is a major global public health challenge. It carries significant morbidity and disease burden globally, as well as locally in Singapore. The age-standardized incidence rate was highest in North America (22.5 per 100,000); while South-East Asia showed a rate of 6.2 per 100,000, based on a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease study 2017.

[2]

According to the Singapore Burden of Disease Study 2010, RA was the 12

th leading cause of overall disease burden in Singapore, as defined by disability-adjusted life years (DALY).

[3] Women are 2–3 times more likely to be affected compared with men. Accordingly, RA is ranked 7th and 16

th leading cause of overall disease burden in females and males, respectively.

[3] Although they can present at any age, the mean age of onset is usually between ages 30–60.

Diagnosing RA

In the primary care setting, general practitioners (GPs) or family physicians may encounter patients with RA in two scenarios:

• A patient presenting with new symptoms suggestive of RA who needs to be referred to a rheumatologist, or

• A patient who is known to have RA on disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) but is coming to see them for another complaint, for example an upper respiratory tract infection or hypertension

Careful history taking and physical examination focusing on inflammatory symptoms is important in diagnosing RA in primary care.

A key aspect to look out for in a patient’s history is symptom(s) suggestive of inflammatory joint pain, rather than mechanical pain. Patients with RA have persistent joint pain that is typically gradual in onset, worsening over several weeks, and improves with activity. This is associated with early morning stiffness lasting more than 60 minutes, joint swelling, warmth, and sometimes, even redness.

Joints and beyond

The joints commonly involved in RA include: small joints of the hands and feet in a symmetric distribution, including the metacarpophalangeal (MCP), proximal interphalangeal (PIP), and metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints while sparing the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints. Other medium to large joints (for eg, wrists, elbows, shoulders, knees, ankles) may also be involved.

Since RA is a systemic illness, patients may have extra-articular manifestations such as subcutaneous nodules, ocular disease (such as keratoconjunctivitis sicca, episcleritis, and scleritis) as well as pulmonary involvement such as interstitial lung disease, which may present with cough and breathlessness. Extra-articular manifestations of RA rarely present in the initial disease manifestations in RA, and they are more common in those who are seropositive. They affect about 50 percent of patients with RA.

Patients may also present with constitutional symptoms such as fatigue, weight loss, or low-grade fever. Less commonly, RA can also have cardiac, neurologic, and haematological complications as well as vasculitis.

Physical examination should focus on detection of active synovitis that results in joint swelling, palpable warmth, and tenderness. It is also important to assess severity of disease by counting the number of joints involved. Targeted examination should be geared towards looking for extra-articular manifestations depending on clinical presentation.

Other tests

Besides patient’s signs and symptoms, the diagnosis of RA can also be supported by laboratory markers and radiological findings.

Laboratory findings that are useful include inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), which may be elevated in the active arthritis phase. Patients may also exhibit thrombocytosis and mild normocytic normochromic anaemia that tend to be correlated with increased disease activity.

In addition, positive rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody (ACPA) in the setting of suggestive clinical settings are also useful to aid diagnosis. ACPA positivity is highly specific (~95 percent) for RA and portends a poorer prognosis.

Plain radiographs of affected joints may show changes such as peri-articular osteopenia and erosions, but we should be aiming to diagnose patients before they have erosions.

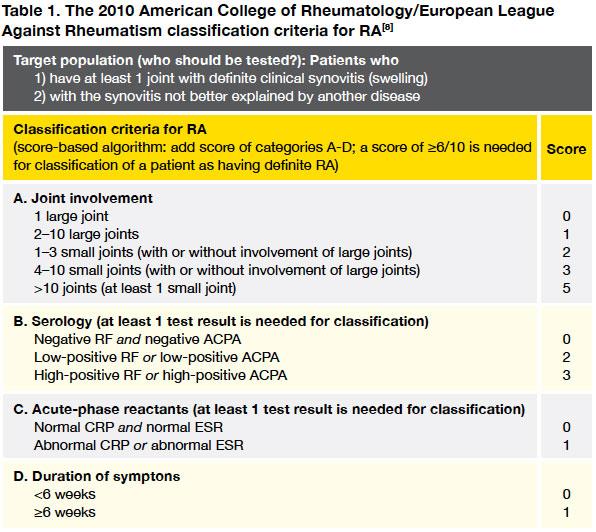

Many doctors will be familiar with the old 1987 ACR criteria for RA, this was revised in 2010 and aims to classify patients with much earlier disease (

Table 1).

Challenges

Patients may present to the primary care very early in the disease course when it may not be clear yet that they have a persistent inflammatory arthritis or the swelling may not be clinically detectable.

Some patients may have atypical joint involvement (eg, mono- or oligo-articular involvement of larger joints as first presentation) where other differentials such as infection or crystal arthritis has to be excluded.

Not all joint deformities are attributable to RA. Osteoarthritis of the hands may have Bouchard’s and Heberden’s nodes, which may cause deformities of small joints of hands and could be mistaken for RA.

In addition, there may not be adequate exposure to rheumatology in medical school or during junior training as these patients tend to be managed in specialist clinics and learners may not encounter many cases during their ward rotations.

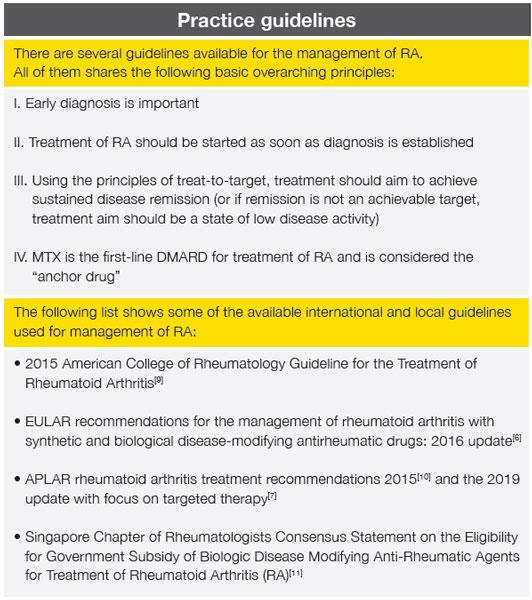

Treating RA

Early diagnosis of RA is important in order to start treatment in the early stages and prevent joint damage and deformities, which in turn would cause loss of function and work disability in our economically viable patients. The concept of therapeutic window of opportunity exists as early as 1992 by Dawwes and Simmons,

[4] and was recently defined as the first 12 weeks after symptoms onset, representing a period before diagnosis is established.

[5]

The key aim of treatment of RA patients is to target towards the best care and should be based on a shared decision between the patient and the rheumatologist.

[6] This should be aimed at maintaining physical functioning and good quality of life through sustained remission, or maintaining low disease activity when remission is not an achievable target.

[10]

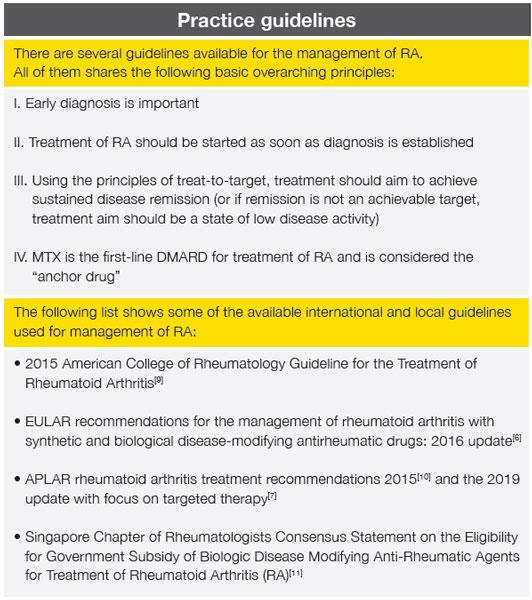

Guidelines suggest that therapy with DMARDs should be started as soon as the diagnosis of RA is made.

[6-7] Early and aggressive treatment with DMARDs has been shown to be effective in altering the clinical course of RA, and slowing or stopping the radiographic progression.

[10] Hence, the importance of early detection and referral to a rheumatologist.

Once-weekly methotrexate (MTX) is the first-line DMARD for RA management. Use of MTX should be supplemented with folic acid once per week, taken a day after MTX. Prior to initiating MTX, prior investigations including complete blood count, liver function and renal function tests, viral hepatitis serology, and chest radiograph should be ordered.

[10]

For patients who are intolerant to MTX, sulfasalazine (SSZ) can be used as an alternative DMARD. It is important to inform patient of potential adverse effects before starting these medications. After starting or changing treatment regimen, it is imperative to monitor and assess these patients every 1–3 months until the disease is stabilized, in remission, or in low disease activity state.

[10]

At the current day and age where effective RA treatment are widely available and accessible, we should not be seeing the ‘classic RA joint deformities’ in our patients. Early specialist referral and thus early and appropriate initiation of DMARD by rheumatologists is crucial to preserve joint structure and thus function. RA patients who are successfully treated are generally symptom-free, are able to maintain function, and lead full and active lives.

Role of GPs

GPs play a crucial role in ensuring that all patients suspected of RA are referred to a rheumatologist and started on DMARDs as soon as possible. Thus, it is important to identify these patients, who may still be early in their disease course, from careful history taking and physical examinations.

In the primary care settings, starting non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or COX-2 inhibitors is reasonable in cases of suspected inflammatory arthritis, as long as there is no contraindication (eg, previous hypersensitivity reaction, renal impairment, state of fluid overload, red flags of known cardiovascular risk factors as NSAIDs can cause an increased risk of serious adverse cardiovascular thrombotic effect).

Low-dose systemic corticosteroids (PO prednisolone <7.5 mg/d) can also be considered. In early RA, the addition of low-dose corticosteroids to csDMARDs leads to a reduction in radiographic progression.

[10] However, it is important to note that the use of corticosteroids may mask physical signs if not clearly documented prior to referral.

In TTSH, referrals from primary care are screened daily so that patients with probable inflammatory arthritis, based on clinical picture and relevant laboratory results such as full blood count (FBC) and inflammatory markers (CRP/ESR), are triaged so that they can be seen as soon as possible in our Early Arthritis Clinic (EAC).

Specific scenarios in primary care

a.Infections while on DMARDs

It is important to treat these infections timely and appropriately to prevent clinical deterioration in view of their immunocompromised state. Most mild infections can be treated in the same way as a patient without RA. Some DMARDs (eg, MTX or leflunomide) or biologics (eg, anti-TNF) would need to be withheld temporarily during period of infection to aid recovery. If patients are clinically septic or develop serious infections (eg, multi-dermatomal zoster), they will need to be sent to the emergency department and admitted to hospital for appropriate therapy.

b. Vaccinations in RA

The ACR and EULAR guidelines for management of RA recommend that:

[9,12]

i. Patients with RA are vaccinated against influenza and pneumococcal pneumonia,

ii. Live-virus vaccines (including measles, mumps, oral poliomyelitis, oral typhoid fever, varicella zoster, yellow fever) should be avoided.

Shared care with rheumatologists

Many rheumatology centres have a shared care programme with primary care centres or family physicians to manage patients with stable RA. If GPs or their patients would like to explore this, do reach out to their rheumatologists to see if this is possible. We would all like to work together to do the best for our patients.

Online resources

Arthritis.org

VersusArthritis

https://www.versusarthritis.org

ACR Website

https://www.rheumatology.org

EULAR

https://www.eular.org/recommendations_management.cfm

References

[1] Silman AJ, Pearson JE.

Arthritis Res 2002;4(Suppl 3):S265–S272.

[2] Safiri S, Kolahi AA, Hoy D, et al.

Ann Rheum Dis 2019;78:1463-1471.

[3] Singapore Burden of Disease Study 2010

https://www.moh.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider5/resources-statistics/reports/singapore-burden-of-disease-study-2010-report_v3.pdf

[4] Dawes PT, Symmons DPM.

Baillière’s Clin Rheumatol 1992;6:117–140.

[5] Burgers LE, Raza K, van der Helm-van Mil AH.

RMD Open 2019;5:e000870.

[6] Smolen JS, Landewé R, Bijlsma J, et al.

Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:960–977.

[7] Lau CS, Chia F, Dans L, et al.

Int J Rheum Dis 2019;22:357–375.

[8] Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, et al.

Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:1580–1588.

[9] Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL, et al.

Arthritis Care Res 2016;68:1-25.

[10] Lau CS, Chia F, Harrison A, et al.

Int J Rheum Dis 2015;18: 685–713.

[11] Teng GG, Cheung PP, Lahiri M, et al.

Ann Acad Med Singapore 2014;43:400-411. (

http://www.annals.edu.sg/pdf/43VolNo8Aug2014/V43N8p400.pdf)

[12] Furer V, Rondaan C, Heijstek MW, et al.

Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:39-52.