Introduction

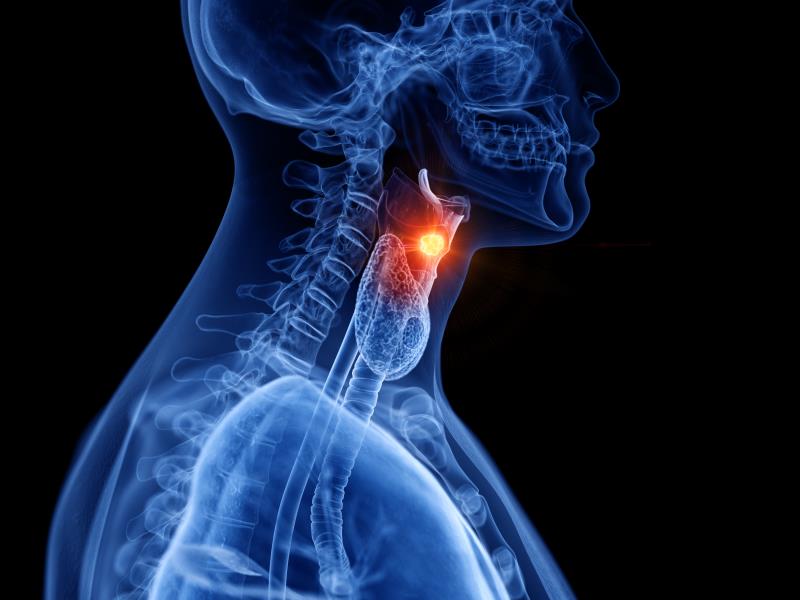

Head and neck cancers encompass a wide spectrum of disease, ranging from carcinomas of the upper aerodigestive tract (oral cavity, pharynx, larynx), to tumours of the skin and salivary glands, to sinonasal malignancies. Additionally, thyroid cancer also falls into the practice realm of the head and neck specialist. The most common type of cancer found along the aerodigestive tract is squamous cell carcinoma (SCC); others include adenocarcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, and mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Details pertaining to each cancer subtype is beyond the scope of this article, and pertinent pointers for general clinical practice will be discussed.

According to the Singapore Cancer Registry 2015, head and neck cancers are among the top ten most common cancers in the population, especially skin cancers such as cutaneous SCC and melanoma which often occur in the head and neck region, and specifically nasopharyngeal carcinoma for men and thyroid cancer for women.

Clinical presentation and risk factors

Many of these conditions can be identified in primary care, and early diagnosis is essential to ensure the best possible treatment outcome for the patient. Red flag signs and symptoms include:

i) lymph nodes or other palpable lumps in the neck

ii) a non-healing white or red patch or ulcer in the mouth

iii) blood stained saliva, sputum, or nasal secretions

iv) voice hoarseness or persistent sore throat

v) difficulty or painful chewing and swallowing

vi) frequent nasal congestion or difficulty breathing

vii) new onset cranial nerve palsies manifested as facial asymmetry, muscle weakness, or numbness of the skin

viii) eye swelling, double vision, or sustained headaches

ix) unilateral tinnitus or decreased hearing acuity

x) suddenly ill-fitting dentures or loose teeth

xi) unexplained fatigue or unintentional weight loss

Some of these may be caused by other benign conditions, but it is still prudent to seek specialist input early, especially if the patient is at high risk for developing head and neck cancer, or if the symptoms or signs persist despite symptomatic treatment or after a period of close observation.

Common risk factors include smoking, alcohol intake, excessive exposure to sunlight (UV rays specifically), betel nut chewing, chronic excessive exposure to nitrosamine compounds, nickel, or asbestos, and in some cases, genetic or hereditary factors.

Diagnosing head and neck cancers

The diagnosis of head and neck cancers would typically require obtaining a tissue sample for histopathological examination. This can be done via fine needle aspiration cytology, core or punch biopsy, or surgical incisional or excisional biopsy. Other tests include staging scans with CT, MRI, or PET scans to establish the local extent of disease, or look for regional spread to the lymph nodes or distant metastasis. Occasionally the patient will also have to undergo endoscopic evaluation for tumours located in areas which are difficult to examine clinically such as the nasopharynx and hypopharynx.

At present, routine screening is not recommended for any head and neck cancer, but health practitioners should maintain constant vigilance to detect the red flag symptoms enlisted above and prompt further investigation. The main challenge in managing conditions of the head and neck is distinguishing benign lesions from pre-malignant ones and recognizing frankly sinister pathologies. Examples would include differentiating a benign melanocytic nevi (mole) from lentigo maligna which may develop into malignant melanoma. Another example is identifying erythroplakia or leukoplakia during an oral cavity examination, as it may become SCC.

A crucial aspect to diagnosing head and neck cancer is thorough physical examination which aside from critical inspection and careful palpation (including the oral cavity), requires otoscopy and evaluation with a laryngeal mirror. GPs can help with early detection by staying alert to insidious presentations such as a vague neck mass or voice changes which patients may not notice themselves, and performing a general head and neck survey as part of their routine examination. Referral to a specialist should be initiated when patients have non-resolving symptoms or when suspicious lesions are discovered. Certain procedures such as flexible nasoendoscopy, high-resolution ultrasound, or needle biopsies can be performed in the specialist clinic, while hospital admission is required for examination under anaesthesia and rigid endoscopy.

Treating head and neck cancers

Principles of head and neck cancer treatment can be categorized broadly depending on the stage of presentation. Early stage cancers (stage I/II) are treated by a single modality alone, usually surgery or radiotherapy. Late stage cancers (stage III/IV) which are locally invasive or with regional nodal disease involvement require multimodality treatment, frequently with the addition of chemotherapy in combination with radiotherapy. In addition, immunotherapy has recently emerged as an alternative to chemotherapy for palliation of recurrent or metastatic SCC of the head and neck.

The main challenge faced in treating head and neck cancers is early detection, as many tumours can be asymptomatic in the early stages. This is essential because late diagnosis tends to be associated with disease in the more advanced stages, which portends a worse prognosis and compounds treatment-related toxicities. Another challenging aspect of care is managing the sequelae of treatment, such as painful mucositis or xerostomia (dry mouth) secondary to radiotherapy which can severely limit oral intake, or postoperative complications such as wound infection or pneumonia which can prolong hospitalization and significantly reduce quality of life. Head and neck cancers and their treatment can lead to temporary or permanent impairment in terms of speech and swallowing. As the tumour is in a prominently visible location, a large mass or surgical scars in this area can markedly alter the patient’s appearance and affect their psychosocial function.

GPs and oncologists play a vital role in helping patients cope with the side effects of therapy, from pre-treatment counselling and managing expectations, to titration of medications for pain or nausea, or supporting lifestyle modifications such as the need for nebulizers and humidifiers for patients after laryngectomy. Follow-up care is also very important to monitor for disease recurrence or locoregional or distant metastasis.

The prognosis of the condition is complex to define numerically without specific distribution into cancer subtype, location, and stage at diagnosis. In general, early stage cancers enjoy better survival rates, for example in the upwards of 70 percent 5-year overall survival for oral cavity SCC (the commonest type) which reduces drastically to approximately 30 percent or less for advanced stages.

Note: While the human papillomavirus (HPV) has been associated with genital lesions and cervical cancers for certain subtypes, there is no strong evidence that vaccination with the current products available can prevent or treat HPV-associated cancers of the oropharynx.

Practice guidelines

Oncologic management in Singapore adheres to international guidelines, which is adjusted to the local population needs, and further customized for every individual patient. A major reference source would be publications from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), an alliance of 28 major cancer centres in the US, which regularly updates guidelines for the treatment of cancer by site, and also provides resources for detection, prevention, and risk reduction strategies, as well as supportive care. NCCN has developed specific adapted versions which take into account metabolic differences, accessibility to technology, and regulatory limits for each region, for instance Asia, Middle East and North Africa, Europe, and South America. There is also an expanding collection of official translations into languages such as Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Spanish, and French which are made available online as well as on mobile applications for free access. The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) also has a very wide range of clinical practice guidelines which can be used for cross-reference to provide patients with the best care option. Most recently, the guidelines for thyroid and cutaneous melanoma were updated and published in the Annals of Oncology.

For clinicians interested in ongoing experimental trials, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) website offers accurate, up to date information on cancer research. The NCI is the US federal government’s principal agency for cancer research and training.

In terms of staging, most healthcare practitioners worldwide use the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) system to describe the extent of disease progression in cancer patients, so that medical information can be homogenized when carried over. Specific to head and neck cancer, the 8th edition of the AJCC staging system was most recently revised in 2017.

To estimate a patient’s risk for postoperative complications, there are tools such as the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) surgical risk calculator by the American College of Surgeons to objectively predict the chance of an adverse event related to surgery. The programme was recently expanded to view geriatric outcomes specific to surgery in the elderly.

Aside from international guidelines and online resources, there is an abundance of information and help available from local hospitals with dedicated cancer centres such as SingHealth to support the ongoing management of these patients. These include patient support groups and survivorship programmes for patients and their families, pamphlets and brochures produced by various institutional clusters for clinicians and caregivers, and regular outreach events such as public health forums and symposiums held for general practitioners. The American Head and Neck Society (AHNS) website offers many useful materials for patient education and YouTube video interviews with real cancer survivors regarding their treatment journey. There are also official endorsed statements on cancer-related topics like HPV vaccination or e-cigarette use, and early detection screening that clinicians can refer to.

Conclusion

In conclusion, head and neck cancers are a complex, heterogeneous group of diseases that occur more often than commonly perceived in the community. It is vital to be alert to the red flag signs and symptoms that these patients present with to increase the rate of detection during the early stages. This affords patients the best chance of cure and minimizes the toxicity associated with multiple lines of therapy. After treatment, ongoing surveillance by primary healthcare teams is crucial to monitor for cancer recurrence. More importantly, community support is essential for these patients who face ongoing lifestyle adjustments in terms of speech and swallowing, and psychosocial issues after their diagnosis.