Bridging gaps: Chan Si Yan on bringing herbs into pharmacy practice

Medical Writer

Chan Si Yan, former pharmacist at the National Cancer Institute and specialist in herbal medicines in pharmacy.

Chan Si Yan, former pharmacist at the National Cancer Institute and specialist in herbal medicines in pharmacy.Modern medicine is often wary of traditional herbal medicines. However, evidence-based use of herbs can sometimes fill in gaps that modern medicine leaves behind. MIMS Pharmacist sat down with Chan Si Yan, former pharmacist at the National Cancer Institute’s Traditional and Complementary Medicines unit, to talk about her experiences in setting up a pharmacy practice that combines traditional and modern elements.

Chan Si Yan hadn’t meant to go into herbal medicines.

“I originally wanted to work in cytotoxic drug reconstitution (CDR),” she said, smiling. “Hospital Ampang was famous for haematology, while the National Cancer Institute (IKN) was known for solid tumours. I thought if I went to IKN after Ampang, I could learn more [in that line].”

But as fate would have it, IKN needed a pharmacist to join their fledgling traditional and complementary medicines (T&CM) unit. While the unit had started in 2013 with non-pharmacological treatments such as acupuncture, plans for a herbal medicine dispensary were added in 2014, and that meant they needed someone qualified to dispense.

Chan seemed like a good candidate. A JPA scholar, she had completed her Bachelor of Pharmacy at the University of South Australia (UniSA), where there had been a strong focus on patient-centred practices and counselling skills in the pharmacy.

She also carried a broad range of field experience with her, having spent her first 4 years as a (provisionally, then fully registered) pharmacist in Hospital Ampang’s Outpatient Department, handling various medication therapy adherence clinics (MTACs) and outpatient counselling services.

“Come to think of it, I feel like those 4 years [at Hospital Ampang] were a lot,” said Chan, laughing. “I started with the warfarin MTAC, but when the diabetic MTAC didn’t have enough pharmacists, they moved me there. Then from three pharmacists, I became the only one in charge … so in the morning I would do the methadone clinic, then the diabetic MTAC in the afternoon, along with part-time work in thalassaemia counselling services and so on.”

Building from scratch

Herbal medicines are stored and prepared behind glass, allowing patients to see the full process.

Herbal medicines are stored and prepared behind glass, allowing patients to see the full process.The new T&CM unit at IKN was headed by consultant integrative medicine physician Dr Lim Ren Jye. Chan described Lim as a ‘hybrid’; trained as a medical officer, he was one of the first MOH staff to be sent overseas to China for further studies in integrative medicine, focusing on incorporating traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) into oncology.

Under Lim’s direction, Chan set up the herbal medicine dispensary, which would focus on TCM-based herbs.

“Before this, Hospital Putrajaya had its own T&CM unit with herbal medicines,” said Chan. “But since currently in government settings herbal medicines are only indicated for patients with cancer, it made more sense to bring that service over to nearby IKN.”

When she started in the unit, Chan knew little about herbal medicines. However, based on her experiences in Hospital Ampang, she started a system of taking a thorough medication history for each incoming patient, including current and past prescriptions, supplements used, any home-grown herbs consumed, allergies, and private practitioners they were also seeing.

“I thought we could begin by figuring out potential adverse interactions or polypharmacy,” said Chan. “Then I started learning more about herbs from TCM practitioners in the unit, and the MOH sent me to introductory TCM courses at Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (UTAR). Once a year, a few of us pharmacists were also sent to Beijing for 2-month courses in a clinical setting.”

She admitted that trying to wrap her head around the basics of TCM and reconciling it with her existing pharmacy training was initially quite difficult.

“Western medicine focuses more on how drug A treats disease A, but TCM often uses the same medication for multiple conditions,” said Chan. “But once you learn to understand the basics of TCM and a different perspective from Western thinking, things get easier.”

Chan also highlighted three issues her team ran into when it came to introducing herbal medicines to an otherwise ‘conventional’ treatment setting at IKN.

“One was that Western-trained doctors tended to equate all herbal medicines with liver or renal failure,” she said. “Another was that patients with cancer … as long as someone tells them there’s a plant they can grow at home or a supplement that supposedly cures cancer, many of them go for it. And then there’s always the question of whether there’s evidence showing a treatment is effective and safe.”

After 2 years in the IKN unit, Chan was sent to Taiwan’s China Medical University for a Master of Science in Pharmacy, specializing in the identification of herbal medicines. She returned to IKN in 2018 and later transferred to a private hospital with Lim in 2019 to help set up a TCM centre.

An eye on safety

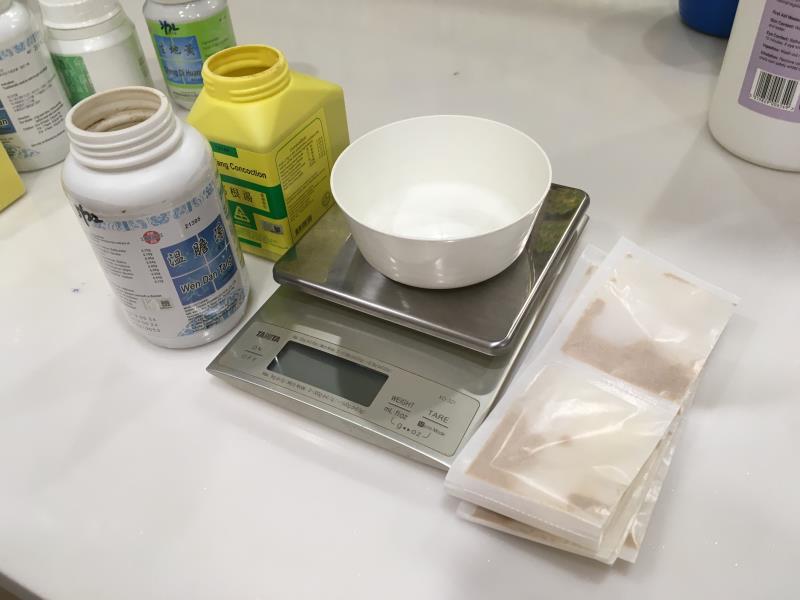

Herbal powders in the dispensary are at higher concentrations than retail products and subject to strict quality control and reporting requirements.

Herbal powders in the dispensary are at higher concentrations than retail products and subject to strict quality control and reporting requirements.At Chan’s current herbal dispensary—modelled after the one she helped set up in IKN—the shelves are lined with rows of bottles, each one with traditional herb names, scientific names, compositions, indications, and contraindications on their labels. All of them contain concentrated herbal powders; some are purely single herbs, while others have multiple herbs blended in specific ratios.

Under her direction, the bottles are stored at optimal humidity and temperature levels. The walls of the dispensary were also made of transparent glass on her request, meaning all prescriptions are prepared in full view of patients. This reassures them that nothing is being secretly added to their herbs, she said.

In one corner of the room is a machine that helps the pharmacists pack the herbal powders into thin paper sachets, each tailored to each patient’s prescribed dose regimen.

“With modern technology, taking herbs is a lot simpler; just tear a packet, put in a cup and drink, rather than boil them for 3 hours. Though we’ve had a few people who tried boiling the bags,” said Chan, laughing.

When she opens a bottle marked ‘Ge Gan Tang Concoction’, the smell is intense.

“These are mainly manufactured in Taiwan with Japanese technology; each batch comes with a certificate of analysis about whether there’s any pesticides, heavy metals, or other contaminants,” said Chan. “The government T&CM units also use these. They’re registered, pre-mixed final products; we don’t use raw herbs here.”

As with all medicines, standardization is a key part of safety. Part of the problem with herbal medicines is how often they’re adulterated with other herbs or drugs such as steroids, she said.

“In olden days, TCM practitioners would dry and prepare raw herbs themselves, but today it’s often harder to confirm their source, safety or quality,” said Chan. “In IKN, when we were considering suppliers, we set a strict list of criteria and supporting documents necessary … it so happened that my Masters supervising professor in Taiwan was already familiar with the various suppliers there and their products, so I could obtain trustworthy contacts.”

Compared to over-the-counter products, the powders in her dispensary are highly concentrated—it takes around 5 g of raw herb to make 1 g of powder—and only available to patients by prescription. The National Pharmaceutical Regulatory Agency (NPRA) classifies them as category T items (Natural Products/Traditional Medicines).

“Registration isn’t compulsory for single-herb powders as they’re considered the same as raw herbs, though companies can opt to do so,” said Chan. “On the other hand, mixed herb formulations are considered products, so registration is compulsory, in case prohibited herbs in the DRGD (Drug Registration Guidance Document) have been added.”

Regardless of registration status, the IKN T&CM unit randomly chooses 10 items each year for local toxicology analysis and comparison with the manufacturer’s certificate. After screening for 100 different drugs, pesticides, heavy metals, and microbes, any unacceptable products are recalled.

Working with proof

Prescribed herbs are packed in the dispensary into single-use sachets according to each patient’s needs.

Prescribed herbs are packed in the dispensary into single-use sachets according to each patient’s needs.Chan noted that a lot more research is needed to build evidence for TCM-based herbal medicines acceptable by Western medical standards.

“I think there’s still a lack of experience in this area among TCM practitioners … how to standardize and make it more evidence based,” said Chan. “In many ways, it’s still a field of knowledge passed down from traditional experience.”

At IKN itself, Chan was part of several research projects in areas such as herb-drug interactions and adjunct herbal therapies in cancer treatment. In 2018, the IKN team published two papers with their findings from a systematic review and a clinical trial on using TCM herbs for radiotherapy-induced xerostomia (dry mouth) in head and neck cancer patients. [Complement Ther Clin Pract 2018;30:6–13; Support Care Cancer 2019;27:3491–3498]

“We don’t have any pharmacological products to treat xerostomia apart from artificial saliva, which is expensive and not sold in many places,” said Chan. “Whereas with certain herbs, there was a visible improvement in their symptoms.”

Other benefits from some herbal treatments include improvements in immune systems and blood cell counts, as well as relieving sleeping problems, at least in patients with cancer, she added.

Chan cited PubMed as a key resource for current evidence in the applications of various herbs. While there are also numerous TCM-focused publications, both the language barrier and a different case report-based system make them more difficult to use, she said.

“For quality, safety, and identification, there are multiple pharmacopoeias from different countries. Even European ones today include TCM herbs,” said Chan. “We use the Chinese Pharmacopoeia, Taiwan Herbal Pharmacopoeia, and the Hong Kong Chinese Materia Medica. For local herbs, we also have the Malaysian Herbal Monograph. They all have information on macro- and microbiology, physical and chemical analysis, existing evidence and so on.”

Looking forward

While Chan’s current role in private practice involves more management, procurement and finance, she still makes time for patient counselling work in the clinic. Both Chan and Lim also continue to assist colleagues in the government with research and teaching.

Asked about her advice to pharmacists dealing with patients and herbal medicines, Chan recommended looking up the evidence for specific herbs first, rather than discouraging all herb use in general.

“Because sometimes we do see some improvement in patients using herbs, especially cancer patients. They do seem to help some of the side effects of chemotherapy and radiotherapy,” said Chan.

She added that the key thing a pharmacist must do is take a thorough medication history and assess possible herb-drug interactions, allergy issues, or even genetic conditions that might have an impact, such as G6PD (glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase) deficiency.

“Also advise them to take herbs 2–3 hours apart from any other medication, and report any adverse effects to the NPRA,” said Chan.

She also hopes that pharmacy degree courses will someday include at least one or two sessions on T&CM to encourage open-mindedness and reduce the misconception that all traditional medicines are to be avoided.

“In a multidisciplinary approach, we [Lim and I] are a bridge between Western and traditional medicine,” said Chan. “The doctor’s side focuses on the effectiveness of herbal treatment, while the pharmacist’s side focuses on safety and quality.”