Vertigo is not a diagnosis but rather a symptom of a myriad of conditions. It is a subset of dizziness or giddiness – a very common complaint among the ageing and often stressed out population. Dr Goh Xueying, Consultant, Department of Otolaryngology at the National University Hospital in Singapore, speaks with Audrey Abella to expound on how to identify vertigo red flags and to diagnose and manage appropriately.

Introduction

Dizziness is a very imprecise term that is magnified in our multicultural population due to differences in cultural contexts. Furthermore, many patients find it hard to describe their symptoms accurately, especially when the history is taken in an unfamiliar language. The actual meaning of ‘dizzy’ may differ in different contexts and cultures, and much may be lost in translation. It is thus important for healthcare professionals to be able to adequately identify the condition.

Vertigo is described as a ‘sensation of spinning’ or an illusion of movement of oneself or one’s environment. Other symptoms that could be described as ‘dizziness/giddiness’ include presyncope (light-headedness), disequilibrium (sensation of being off balance), headaches, sleepiness, or nausea.

Vertigo occurs as a result of dysfunction of the vestibular system or cerebellum. This dysfunction results in the abnormal and often involuntary movements of the eyes resulting in the illusion of movement (spinning). This is mostly accompanied by an autonomic response of nausea, vomiting, tachycardia, and elevated blood pressure.

Balance is maintained by inputs not only from the vestibular system or cerebellum but also from the visual system and somatosensory proprioceptive inputs from the joints and limbs. Patients with deficits in proprioception or vision problems have a reduced ability to compensate for vestibular dysfunction.

Diagnosing vertigo

Vertigo is a presenting symptom for many conditions. After ascertaining that the symptom is indeed vertigo, the medical practitioner would need to look for red flags that would indicate a referral to the emergency department or specialist for further evaluation and management.

Red flags include:

· Other neurological deficits (limb weakness, cranial nerve deficits)

· Loss of consciousness

· Associated hearing loss or tinnitus (usually unilateral)

· Ear discharge or pain

· Chest discomfort or breathlessness

· Acute persistent disabling vertigo not responding to treatment in the form of vestibular suppressants

In the absence of red flags, the next step would be to determine if the vertigo is an acute occurrence or a recurring problem. Identifying the duration of each vertigo episode may establish the diagnosis. The physician should also probe further about history of headaches and migraines, associated ear symptoms (hearing loss, tinnitus, and ear discomfort or discharge), and recent head injuries or viral infections.

History

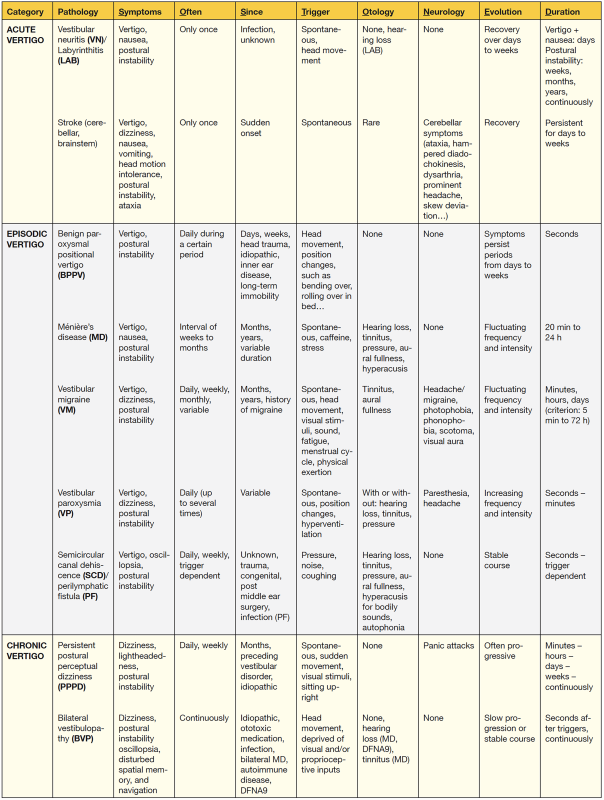

Wuyts et al formulated a framework to guide history-taking in a patient with vertigo (Table 1). They used the acronym ‘SO STONED’ – Symptoms, Onset, Since (total duration), Trigger, Otology, Neurology, Evolution, Duration (of each attack) as an aide for the key points required in a dizziness history.

Table 1: “SO STONED”: Common Sense Approach of the Dizzy Patient [Front Surg 2016;3:32]

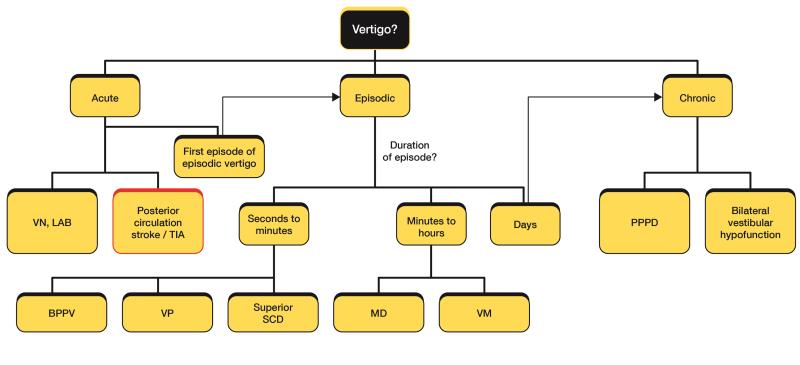

A simplified diagnostic algorithm based on history for a patient presenting with vertigo.

[Diagram courtesy of NUH]

Examination

After history taking, examination would help to confirm the diagnosis and guide management. A directed dizziness examination would start with assessment of the patient’s gait, followed by examination of extraocular movements and observation of any nystagmus. The patient is screened for any cranial nerve deficit. Otoscopy should be performed to look for ear conditions that may cause dizziness (eg, acute otitis media, cholesteatoma, herpes zoster).

Four important tests to be conducted to accurately evaluate vertigo are a cerebellar examination, a head impulse test, cover-uncover test, and the Dix-Hallpike Test.

Kattah et al described the simple 3-step HINTS examination (Head Impulse, NysTagmus , Skew Deviation) to help determine if a patient presenting with acute vertigo may be suffering from a stroke. In this study, the authors found that a patient with a ‘benign’ HINTS test (abnormal head impulse test, unidirectional horizontal nystagmus, absent skew deviation on cover-uncover test) rules out a stroke with 96 percent specificity.

In a patient presenting with acute vertigo, a general practitioner (GP) might find it difficult to diagnose a patient who may be acutely unwell with nausea, vomiting, and unsteadiness. Hence, many GPs might choose to refer these acutely vertiginous patients to the emergency department for closer monitoring and acute treatment.

GPs may be able to diagnose patients with vertigo that is episodic or mild-to-moderate in intensity through a good history and examination. At times, it may be difficult to clinch a diagnosis at the first review, but with time and follow-up, the diagnosis will become more obvious as the symptomatology of the condition evolves.

Treating vertigo

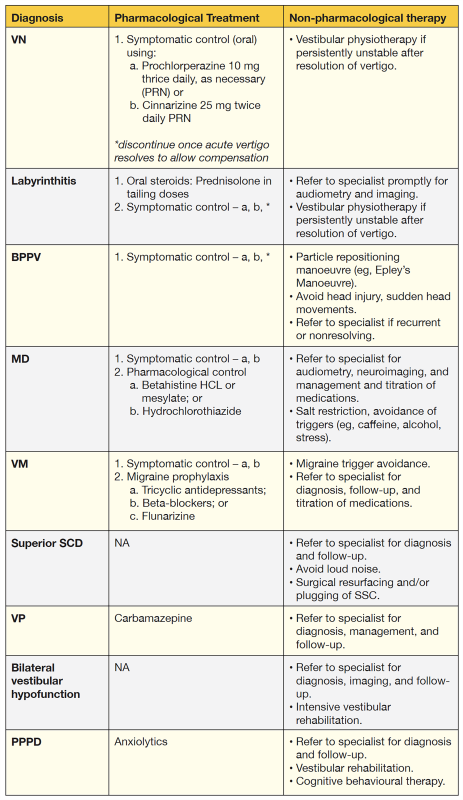

Treatment depends on the diagnosis of the condition causing vertigo. Table 2 outlines the brief treatment strategies for the different diagnoses.

Table 2: Treatment strategies

Conclusion

Vertigo is a symptom, not a diagnosis. A good history and physical examination would usually allow the physician to rule out red flags and to narrow the differential diagnoses for subsequent treatment or referral.