At a Menarini-sponsored symposium held during the Asian Pacific Society Congress, renowned cardiologist Prof John Camm provided the latest evidence for chronic stable angina with or without concomitant diseases, with a special focus on the antianginal agent ranolazine and combination therapies. The event was chaired and moderated by Dr Dante Morales from the University of the Philippines College of Medicine.

Personalized medicine is paramount even in the arena of chronic stable angina. In western countries, about 30,000-40,000 cases per million have chronic stable angina.1 The prevalence increases with age, with the incidence slightly higher in women than in men. This is expected to increase because of the ageing population, the epidemic of obesity, and other risk factors.1 Clearly, chronic stable angina is a problem that deserves our attention as cardiologists.

Antianginal agents have different modes of action

When personalizing treatment for patients with chronic stable angina, it is important to note that various antianginal agents work differently.

β-blockers, for example, exert their effect predominantly on the β1-adrenergic receptor. Calcium-channel blockers (CCB) affect the calcium ion channel and the availability of calcium within the cell. Nicorandil, a mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium channel opener, affects the smooth muscles directly. Trimetazidine also affects mitochondrial function, particularly oxidation of free fatty acids. Nitrates predominantly affect the smooth muscle cells, while ivabradine affects the If current channels.2

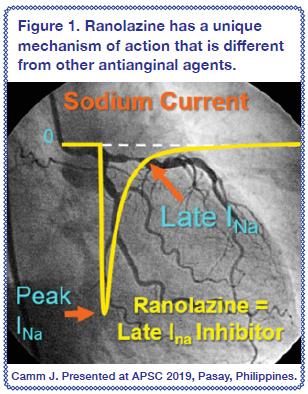

Ranolazine is unique, for it specifically inhibits the late inward sodium ion currents in ischaemic cardiomyocytes, which then reduces calcium ion accumulation (an important contributor to the pathogenesis of angina) and improves left ventricular function without altering blood pressure (BP), heart rate, or vascular resistance [Figure 1].

Ranolazine effective for angina

In a meta-analysis of 9,223 patients with coronary artery disease (CAD), treatment with ranolazine reduced the weekly angina frequency by 31 percent and the weekly sublingual nitroglycerin use by 47 percent. Ranolazine also prolonged exercise duration, time to onset of ischaemia, and time to onset of angina without substantial effects on BP and heart rate.3

In a detailed Cochrane database analysis that included several outcomes, add-on ranolazine significantly reduced the weekly angina frequency vs placebo (mean difference [MD], -0.66).4

Ranolazine in chronic angina with concomitant diseases

Favourable anti-ischaemic and antiarrhythmic effects

The pharmacological properties of ranolazine and evidence from clinical trials suggest that ranolazine has favourable anti-ischaemic effects independent of reductions in BP or heart rate. In a subanalysis of patients with prior chronic angina in MERLIN-TIMI (Metabolic Efficiency With Ranolazine for Less Ischaemia in Non-ST Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes), the primary endpoint of a composite of cardiovascular (CV) death, MI, and recurrent ischaemia was less frequent in those treated with ranolazine vs placebo (hazard ratio [HR], 0.86; p=0.017).5

It is known that the pathological basis of ischaemic heart disease differs between the sexes, and may affect response to therapy. Compared with placebo, ranolazine significantly reduced recurrent ischaemia in women (HR, 0.71; p=0.002), suggesting that ranolazine is efficacious in women with ischaemic heart disease.6 The totality of evidence implies that the anti-ischaemic effects of ranolazine are beneficial in both men and women.6

Favourable antihyperglycaemic and metabolic effects

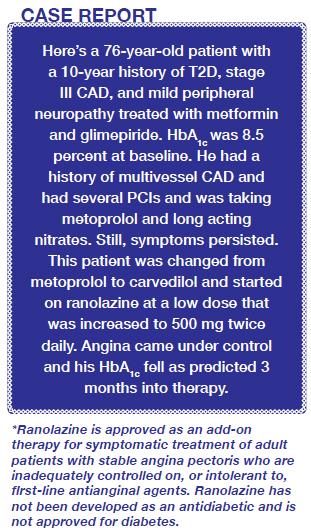

Another unexpected finding with ranolazine was the HbA1c reduction in patients with chronic angina and diabetes. In a post hoc analysis of the CARISA trial, ranolazine 750 mg twice daily significantly reduced HbA1c by 0.48 percent vs placebo (p=0.008).7 A similar finding was seen in MERLIN-TIMI 36 wherein worsening hyperglycaemia was higher in those treated with placebo vs ranolazine (relative risk [RR], 0.63; p<0.001).7 A greater proportion of patients with diabetes achieved HbA1c <7% when treated with ranolazine compared with placebo (59% vs 49%; p<0.001).8

In the TERISA study of patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) and chronic angina despite treatment with up to two agents, ranolazine reduced weekly angina frequency (p=0.008) and weekly nitroglycerin use (p=0.003) vs placebo.9 This was supported by an exploratory analysis showing that the more significant the diabetes (HbA1c>8), the greater the reduction in the incidence density ratio of angina, suggesting that angina responded better in those with higher HbA1c levels.9

Clearly, ranolazine exerts positive antihyperglycaemic and metabolic effects in angina patients with uncontrolled HbA1c.10

Caution for clinicians

One important consideration when using ranolazine in CAD patients with diabetes is that ranolazine interacts with metformin. Metformin is excreted using the OC transporter and that is inhibited by ranolazine. Hence, dose adjustments may be warranted to safely use both medications.11

Potential role in microvascular angina

Evidence also supports ranolazine’s possible role in the management of primary microvascular angina (MVA), ably reducing mechanical dysfunction, and demonstrating anti-inflammatory or antioxidant effects, which may improve endothelial function in patients with T2D or stable CAD.12 Additionally, ranolazine also improves glycometabolic homeostasis.12

In one study of MVA patients inadequately controlled on standard anti-ischaemic therapy, ranolazine and ivabradine both improved Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ) items and EuroQoL score vs placebo (p<0.01 for both), but ranolazine was more effective on some SAQ items and EuroQoL scale (p<0.05).13 A recent review of this outcome in patients with ischaemia but no obstructive coronary artery disease (INOCA) showed that QoL was best improved with ranolazine and ACE inhibitors, with other antianginal agents showing little or no evidence of efficacy.14

Ranolazine reduces myocardial damage during PCI

Similarly, pretreatment with ranolazine in patients with stable angina scheduled for elective coronary intervention significantly reduced myocardial injury during percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).15

Costs of care, revascularization rates lower with ranolazine

In an analysis of insurance claims, ranolazine users had lower revascularization rates and total costs of care vs nitrate or β-blockers/CCB users.16 This was supported by another study showing that ranolazine use was associated with less revascularization and all-cause and CV-related healthcare utilization vs traditional antianginal medication.17

Combination therapies with ranolazine

In an analysis of combination therapies in patients with stable angina refractory to first-line therapy, ranolazine added to β-blocker or CCB demonstrated benefits across all exercise and clinical outcomes assessed.18 Ranolazine increased exercise capacity and provided additional antianginal relief even in those with severe chronic angina already taking atenolol, amlodipine, or diltiazem and maintained a favourable safety profile over 1-2 years of treatment.19

Ranolazine in the ESC guidelines

The 2013 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines on the management of stable CAD recommend the use of short-acting nitrates plus first-line drugs such as β-blockers and/or calcium channel blockers (CCBs) to control heart rate. Ranolazine, long-acting nitrates, ivabradine, nicorandil, or trimetazidine may be added as a second-line option depending on heart rate, BP, and tolerance. In selected patients, second-line agents may be used as a first-line treatment according to comorbidities or tolerance.20 The 2016 NICE guidelines for stable angina management have similar recommendations. The choice for a monotherapy or combination therapy depends on comorbidities, contraindications, patient preference, and drug costs. A third antianginal drug may be considered only when symptoms are not controlled with two agents or when awaiting revascularization, or revascularization is inappropriate or unacceptable.21

Why some antianginal agents are positioned as first-line vs second-line in the guidelines may not be because of the level of evidence or efficacy but because of the long history of its use and cost. First and second-line antianginal agents are similarly effective in reducing symptoms, with varying levels of recommendations from the ESC and the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA). However, there was no recommendation on which drug should be given to which patient and the best possible combination.

‘Diamond’ approach to treatment

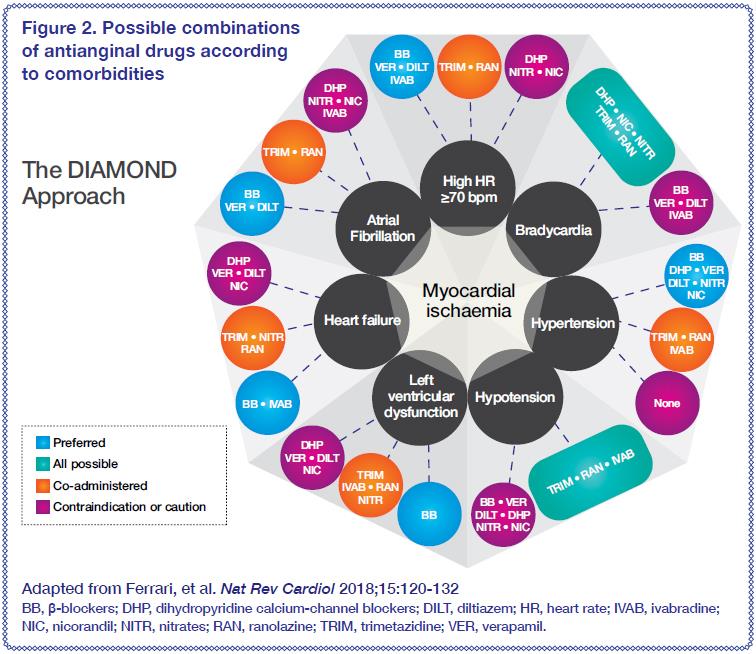

Myocardial ischaemia has different manifestations and so does its symptom, chronic stable angina. Antianginal drugs have different haemodynamic effects and benefits that make management of angina challenging. A more individualized strategy, the ‘diamond’ approach, with the patients’ comorbidities and mechanisms of angina at the centre of therapy, may guide clinicians on the best antianginal choices for their patients [Figure 2].22

Conclusion

Ranolazine’s efficacy as an adjunct therapy to other antianginal agents is supported by current guidelines and RCTs. Diabetic patients with angina appear to respond well to ranolazine and so do patients with AF and angina, warranting further investigation.