Members of the Hospital Pulau Pinang Endocrinology and Diabetes unit at a World Diabetes Day event. L-R: Dr Shaunty Velaiutham, consultant endocrinologist; Lim Phei Ching with fellow DMTAC pharmacist Wong Te Ying; and Jason Kam, endocrinology ward pharmacist.

Members of the Hospital Pulau Pinang Endocrinology and Diabetes unit at a World Diabetes Day event. L-R: Dr Shaunty Velaiutham, consultant endocrinologist; Lim Phei Ching with fellow DMTAC pharmacist Wong Te Ying; and Jason Kam, endocrinology ward pharmacist.Diabetes is a complex disease that is best treated by a multidisciplinary team of healthcare professionals. But even with their help, patients with diabetes often struggle to comply with a bewildering array of medications at home. In conjunction with World Diabetes Day on 14 November, Lim Phei Ching speaks with MIMS Pharmacist about her experiences in 13 years as a pharmacist in Hospital Pulau Pinang’s Diabetes Medication Therapy Adherence Clinic (DMTAC).

How did you get into DMTAC?

I started DMTAC when Hospital Pulau Pinang first initiated the service in 2006. Puan Zubaidah Che'Embee, our current TPKNF (Timbalan Pengarah Kesihatan Negeri Farmasi) initiated the service in the Pharmacy Department. At the time I was asked to join the DMTAC clinic together with another colleague.

When we first started, we had to sit at the patient waiting area together with the patients, trying to review their drugs, getting to know their adherence, what behaviours stopped them from complying, and educating them. Years later, we pharmacists have our own room in the endocrine clinic.

Lim conducts one-on-one counseling sessions with patients with diabetes referred to her DMTAC clinic.

Lim conducts one-on-one counseling sessions with patients with diabetes referred to her DMTAC clinic.Take us through your work.

DMTAC pharmacy is more about clinical practice and more patient-centred. It’s a paradigm shift for the pharmacy profession. We used to be the end point, whereby the patient would see the doctor and then subsequently come to the pharmacy to get their drugs dispensed. With this programme, during the follow-up with the doctor, the patient comes to the DMTAC pharmacist first.

To start with, we do a medication review for any interactions, polypharmacy, drug-related problems or barriers that stop the patients from being compliant. Then we suggest interventions to help the patient. These can be either ‘stop drugs’ if the drugs are already not relevant; ‘adding drugs’, or ‘counselling the patient’. Especially in those cases that may require insulin, we counsel the patient to accept insulin injections.

As you know, patients can often live with multiple comorbidities; they may have multiple clinic follow-ups with the urologist, cardiologist, neurologist, nephrologist and endocrinologist. But the drugs from different clinics may differ in terms of dose, or they may be from the same class of drugs but of different types. We’ll try to determine any interactions, and then inform the doctor, so the doctor will change the prescriptions to avoid interactions. Then the patients see the doctor. After that, they come back to us for counselling, and then we schedule the next follow-up.

The patients meet the pharmacist every month; in certain cases, every 2 weeks, or every 2 months and in between the doctors’ follow-ups. We teach them how to manage their disease and monitor their blood sugar.

During pharmacy follow-ups, we also titrate patients’ insulin dosage—in agreement with the consultant endocrinologist—based on their diet, and then we counsel them on lifestyle changes, exercise, diet, their disease comorbidities and how to take care of themselves, in the hope that they understand and subsequently can self-manage their disease. We teach them how to determine hypoglycaemia, and to self-treat before they faint; in some cases, we counsel a family member so they can manage hypoglycaemic episodes at home.

In the end, [DMTAC] involves a shared decision-making, and it’s a shift to involve patients in the final decisions of their drug therapy and management.

Lim with doctors, medical officers and endocrine trainees of Hospital Pulau Pinang’s Endocrinology and Diabetes unit. L-R first row: consultant endocrinologists Dr Shanty Velaiutham, Dato' Dr Nor Azizah Aziz, Dr Khaw Chong Hui, and Dr Lim Shueh Lin.

Lim with doctors, medical officers and endocrine trainees of Hospital Pulau Pinang’s Endocrinology and Diabetes unit. L-R first row: consultant endocrinologists Dr Shanty Velaiutham, Dato' Dr Nor Azizah Aziz, Dr Khaw Chong Hui, and Dr Lim Shueh Lin.What’s the longest you’ve seen the same patient for?

There are discharge criteria; we can discharge a patient after eight visits with us, or if those patients have already achieved a good blood sugar control (HbA1c). For those patients who reach HbA1c <7.5 twice, we can discharge them. There’s some who can even get their HbA1c <6.5; we discharge them within 4 or even 3 months.

The longest patient that I’ve seen had been with us for 2 years. His HbA1c levels never came down; it was due to his uncontrollable appetite. Diabetes is a food-related disease and also an inherited disease, so it depends on what the family’s culture is and what their nutritional beliefs are.

What do you find most challenging about your work?

Mainly … [diabetes treatment] is behaviour-related, and it’s impossible to change someone’s behaviour or habits over days or within a short period of time. It’s hardest especially when we ask patients to change their diet and exercise habits.

Do you counsel on lifestyle changes or more strictly on medication?

Our counselling is more on medication, but we try to tailor drugs towards the patient’s lifestyle, especially something like insulin, which we titrate based on their diet. If let’s say the patient is willing to make a change of lifestyle, we definitely need to adjust the patient’s medication dosage. Because if patients with high carbohydrate intake—lots of rice—suddenly want to cut down their rice intake to the quarter-plate portion that their dietitian suggests, we need to reduce the insulin or drug dosage to prevent hypoglycaemia or unwanted side effects.

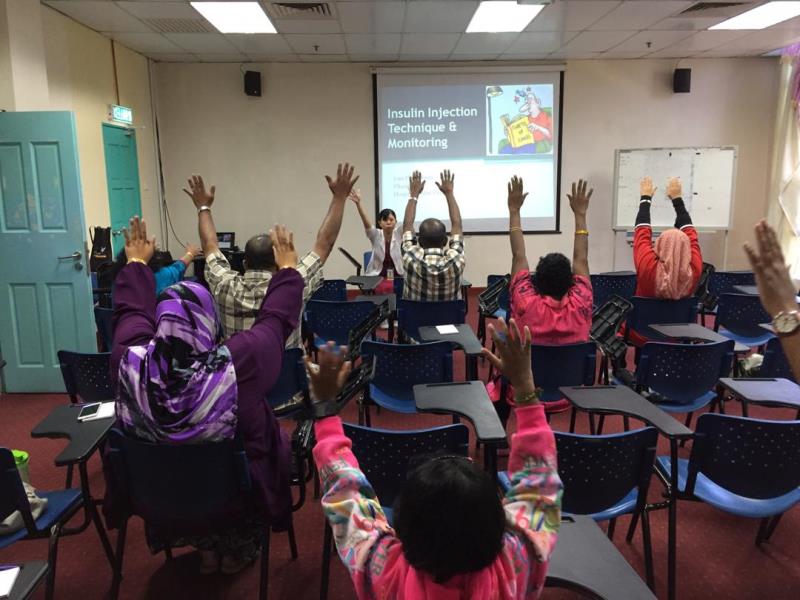

Lim conducting an exercise session prior to a talk at a group patient programme.

Lim conducting an exercise session prior to a talk at a group patient programme.Any particularly memorable cases?

I had one patient—an old uncle—who initially had very poor control when he came to us because he didn’t know what drugs he was taking and couldn’t remember them [when informed]. Anything you asked him about, he would just answer, “I don’t know, I’m illiterate, I didn’t go to school.”

When we tried to counsel him on his drugs, it was very difficult, until one day I just gave him a pillbox and filled one of the columns for him. Then I gave him another column, asked him to fill it himself, and I taught him about [each of] his drugs’ indications, their uses, etc.

When he came the next month, I had to assess his knowledge on his medication. When I started the assessment, he suddenly brought out a magnifying glass.

“Why did you bring that for? And why are these two columns (in the pillbox) totally empty?” I asked.

“Because I knew I was coming for an exam, I needed to empty them, otherwise later you’d say I was plagiarizing,” he said.

“Okay, fine,” I said. “So tell me how you handle all this; how you take your drugs, their indications, everything?”

And it was totally 100% correct. During the third visit, when he came to me, he could even label his medication by himself. When I tried to show him how, he said “I know how to already, I can write.” I asked him to show me how he did it, and he could! Subsequently, because of his compliance and adherence to the medication, his control was very good for a geriatric patient—keeping his HbA1c less than seven—and that has lasted for a few years since.

There was another memorable experience I had; the nephrologist had referred a lady to [the DMTAC clinic] because of multiple hypoglycaemia events. She had very bad diabetic retinopathy, to the point where she couldn't see. At the time she came to us, the doctor had changed her regimen to three types of insulin with three of the same insulin pens.

Initially when I interviewed her, she said there was nobody to help her in the house. We thought that meant she was living alone. After a month, we went to her house to visit her, just to make sure that she was taking her medication and insulin correctly. When we went there, we realized she was in fact living with her husband, who is also blind due to retinopathy.

So how did we help her? By using a shape code. We cut papers into different shapes—round for morning, triangle for lunch, and a moon shape for dinner—and stuck them on the insulin pens and boxes. She could touch the shapes to understand how to administer her insulin correctly.

Well, she now injects correct insulin at the correct time, and in fact there’s been no hypoglycaemia for the past 1 month. Her control is good, and in fact—now she can see again. Even her chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage is still being maintained at stage 4, and not worsening, so it’s been a good thing.

Lim and Dato’ Nor Azizah Aziz (3rd from right), consultant endocrinologist and head of the Endocrinology and Diabetes Unit, with nurses from the unit.

Lim and Dato’ Nor Azizah Aziz (3rd from right), consultant endocrinologist and head of the Endocrinology and Diabetes Unit, with nurses from the unit.What do you find satisfying about DMTAC work?

When you see your patients becoming healthier, and getting their HbA1c under control, that’s the most satisfying thing. Also, since diabetes can be inherited, when we see younger persons with diabetes—children, teenagers or young adults—we advise them to bring their siblings or other family members to screen for diabetes as well.

In fact, sometimes at the end of the day we’ve got the whole family in our clinic. But when it’s a whole family, it’s easier in a way. We teach the chef of the house—especially the mother—about what they need to have in terms of drugs, lifestyle and diet all together. It’s impossible to separate them, that’s the thing.