Zolpidem and zopiclone are among the most frequently prescribed hypnotics. They are the only z-drugs available in Hong Kong. Zopiclone is used in Europe, while eszopiclone, a stereoisomer, is used in the US. The European Medicines Agency determined that there is no advantage of eszopiclone over zopiclone. Both zolpidem and zopiclone are believed to be good substitutes for benzodiazepines, with less tendency for abuse, addiction, dependence or withdrawal. (However, this view is now under dispute.)

The two drugs are very similar. They are cheap, effective, well tolerated, and have short half-lives. But are they the same, or should a doctor choose one over the other when prescribing to a patient?

Zolpidem is an imidazopyridine compound that acts as an agonist on the alpha-1 subtype of the benzodiazepine site of the GABAA receptor. Thus, it has a specific effect on sedation and has no myorelaxant, anxiolytic and anticonvulsant properties. These give it a theoretical advantage over zopiclone, for instance, in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea.

Zopiclone is a cyclopyrrolone compound that acts on alpha-1 and more broadly, on other alpha subtypes of the benzodiazepine site of the GABAA receptor, making it more similar to a benzothiazine drug.

In response to reports of abnormal behaviours during sleep after taking these drugs, the US FDA imposed a black box (ie, the most serious) warning in April 2019 cautioning on the use of z-drugs: “Serious injuries and death from complex sleep behaviours have occurred in patients with and without a history of such behaviours, even at the lowest recommended doses, and the behaviours can occur after just one dose. These behaviours can occur after taking these medicines with or without alcohol or other central nervous system depressants that may be sedating, such as tranquilizers, opioids and antianxiety medicines.”1

So far these are the similarities. Now let us look at the differences.

The FDA identified 66 cases of complex sleep behaviours that reported serious injuries or death after taking z-drugs (zolpidem, n=61; eszopiclone, n=3; zaleplon, n=2) in 26 years (1992–2018).1

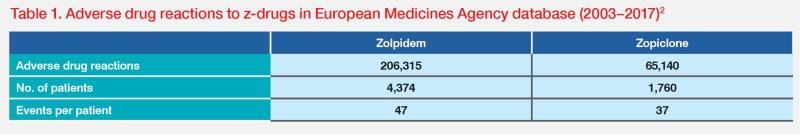

A study analyzing adverse drug reactions to z-drugs using 2003–2017 data from the European Medicines Agency database indicated that the relative risk of zolpidem over zopiclone was 1.27.2 (Table 1)

Further analysis revealed that the tendency for misuse, abuse and withdrawal was higher among zolpidem users than zopiclone users, but the reverse was true for overdose. The rate of fatal outcome was 20.3 percent for those who overdosed on zolpidem compared with 9.33 percent for those who overdosed on zopiclone.2

In a paper published in 2020 that reported on a 12-year, population-based, retrospective cohort study conducted in South Korea in 2002–2013 involving over 1 million people, the adjusted hazard ratio of suicides associated with the use of zolpidem was 2.01.3

In a systematic review and meta-analysis in 2022, a significantly increased risk of suicide or suicide attempt was found among zolpidem users compared with nonusers, with a pooled relative risk of 1.88. Furthermore, an increased risk of suicidal death was observed among zolpidem users compared with nonusers, with a pooled relative risk of 1.82.4

In Australia, the Adverse Medicine Events Line reported 29 cases of neuropsychiatric reactions, including two deaths in the 3 years prior to November 2005. Twenty-six cases were related to zolpidem use and three to zopiclone.5 The greatly increased risk of zolpidem cannot be attributed to higher prescription, as shown in another paper reporting that prescription of zopiclone exceeded that of zolpidem in Australia every year from 2011 to 2018.6

Zopiclone is also the most commonly used hypnotic in the UK and in Alberta, Canada.7,8 In Alberta, zopiclone was prescribed to 47.4 percent of all patients using hypno-sedative medications.9 In Canada, zolpidem is only available as a sublingual tablet, and it is not covered by government insurance payment. Hence, its use is minimal.

A review of 29 psychoactive drugs (including the three z-drugs) in 2018 showed that zolpidem had the strongest evidence for medication-induced sleepwalking (complex sleep disorder).10

In a comparison between zolpidem and zopiclone in elderly patients with Alzheimer’s disease, zopiclone was found to increase the main nocturnal sleep duration by 81 minutes, but there was no improvement for zolpidem.11

Administration of eszopiclone, but not zolpidem, to adult guinea pigs increased the mean duration of episodes of non–rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep.12 NREM sleep promotes repair and regrowth of the body, building of bone and muscles, strengthening of the immune system and memory consolidation.

As with any other medication, drug interaction must be considered, as many patients are taking psychotropic drugs at the same time. The main concerns are competition in protein binding and the CYP450 enzymes. Coadministration with fluoxetine increased the half-life of zolpidem by 17 percent, and coadministration with sertraline increased zolpidem’s peak concentrations by 43 percent.13 Co-administration with fluvoxamine and valproic acid has been incriminated as the cause of sleep disorders.14 Two patients fatally shot their spouses after taking zolpidem with paroxetine.15

For my own clinic, I do not prescribe any zolpidem. I advise all my patients and colleagues not to take it. I have seen many cases (including doctors) who got up to cook at night and then forgot to switch off the gas stove, or who drove out and returned safely to their car parks but had amnesia for the episode.

Lesson: When prescribing z-drugs, your informed choice matters.

References:- https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-adds-boxed-warning-risk-serious-injuries-caused-sleepwalking-certain-prescription-insomnia

- Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2019;22:270-277.

- Sci Rep 2020;10:4875.

- Psychiatry Res 2022;316:114777.

- BMJ 2005;331:1169.

- Br J Gen Pract 2021;71:e877-e886.

- BMJ 2019;365:l2165.

- Can J Psychiatry 2006;51:287-294.

- Can Fam Physician 2007;53:2124-2129.

- Sleep Med Rev 2018;37:105-113.

- Neuropsychopharmacology 2022;47:570-579.

- Sleep 2008;31:1043-1051.

- AMBIEN Prescribing Information, 2022.

- Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2010;12:PCC.09r00849.

- Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2012;14:PCC.12br01363.

Clinical notes in Psychiatry and Neurology

Complex sleep behaviours and sleepwalking: The confusion of two confusional states

Parasomnias are disorders characterized by abnormal behaviours occurring in association with sleep. They are divided into two types:

- Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behaviour disorders, including restless leg syndrome, sleep paralysis, and nightmares

- NREM sleep behaviour disorders

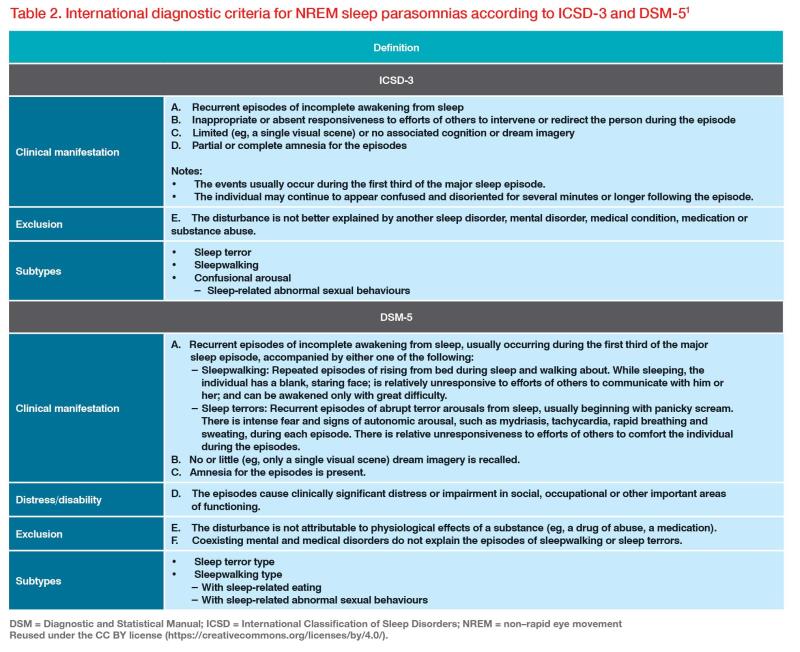

Table 2 provides details on types of NREM sleep disorders as defined by ICSD-3 (International Classification of Sleep Disorders) and DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual).1

Both classifications of NREM sleep disorders include sleepwalking and exclude conditions that are due to medication use. In DSM-5, there is a differential diagnosis of medication-induced complex behaviours. In sleepwalking, the patient is deeply asleep and cannot be easily awakened. There is complete amnesia for the event. The patient will not answer questions or follow instructions. They can sometimes perform complex behaviour such as driving a car, although they can fall off a balcony and injure themselves. Their awareness is diminished, so they are in a confused state. They are totally amnesic for the episode. When they become awake, they will become totally awake quickly.

In complex sleep behaviour due to drugs (frequently z-drugs), the patient is not in a state of sleep. They are in a state of decreased consciousness. They may be able to react to the environment, such as answering some questions and driving a car with or without accident. Their level of consciousness may fluctuate and this may last for a long time (eg, days). They may have total or partial amnesia.

Here is the issue: The two different conditions are often confused, even in learned journal papers. Many authors talk about sleepwalking or sleep driving after taking z-drugs, but in fact these are complex sleep behaviours. The word ‘sleep’ here means that the abnormal behaviour occurs after the patient goes to sleep, not that the patient is in a state of sleep.

It is important to make the distinction. Quoting a paper from Sleep Medicine Reviews: “The term ‘sleep driving’ should be reserved for patients who have signs, symptoms and history consistent with sleepwalking and related disorders. Driving while impaired following abuse or misuse of z-drugs or other sedative hypnotics should not be attributed to sleep or sleepwalking. The data reviewed in this article suggest that the majority of cases The data reviewed in this article suggest that the majority of cases should be labelled simply as ‘drug-related impaired driving’.”2

References:- Diagnostics (Basel) 2023;13:1261.

- Sleep Med Rev 2011;15;285-292.