A virus with the strange-sounding name chikungunya made newspapers and the television last year. Like dengue, this seemingly new disease entity is caused by an arthropod-borne virus as well as shares similar clinical features with its more popularly recognized cousin.

Dr. Salvacion Gatchalian of the Research Institute of Tropical Medicine and the Pediatric Infectious Disease Society of the Philippines described chikungunya in relation to dengue to help clinicians approach their patients who may have either.

Both dengue and chikungunya viruses are spread by the mosquito Aedes aegypti as well as by Aedes albopictus. As they share common vectors, these two may co-circulate in the same parts of the globe. Since dengue was first recognized in the Philippines in 1954, it has been endemic in this country. Chikungunya was also identified in the country in 1967, but has been largely missing from public consciousness until an outbreak of the disease last year.

The two have similar incubation periods of 1 to 12 days with an average of 2 to 4, but the onset of illness is frequently more abrupt with chikungunya.

With chikungunya, severe symptoms occur earlier and the duration of illness is shorter with almost half experiencing fever lysis within 72 hours of onset. Its severity ranges from a mild febrile illness to severe polyarthralgia and arthritis with rash.

“The clinical triad, generally, that is defined for chikungunya is fever, maculopapular rash [and] arthralgia. But, actually, several studies have shown that if it’s just arthralgia… then it is not chikungunya. There must be an associated arthritis,” explained Gatchalian.

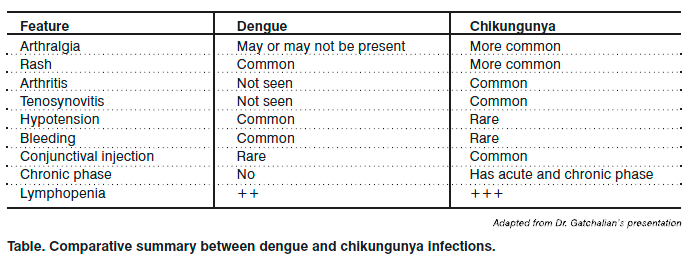

Among the range of possible clinical manifestations, those most significantly associated with chikungunya rather than dengue are arthralgia, arthritis, tenosynovitis and conjunctival injection. More commonly seen in dengue but uncommon or rare in chikungunya are hypotension and bleeding (usually on the fifth to the seventh days) and shock.

The joint symptoms seen in chikungunya are most disabling and frequently symmetrical. More than one joint is typically affected, involving fingers, wrists, elbows, ankles, knees and toes. While some fully recover, up to 57 percent have reported persistent or recurrent symptoms at 15 months after initial infection and up to 12 percent at 3 years. Children are at greatest risk for severe joint disease.

While the petechial rash is more common in hospitalized dengue patients, the maculopapular rash occurring during the fever episode is more prominent in chikungunya. It appears in the trunk and extremities but may also involve the face, palms and soles, lasting for 2 to 3 days. Aphthous-like ulcers, vesiculobullous eruptions with desquamation and vasculitic lesions, are also possible.

The role of laboratory tests

According to Gatchalian, leukopenia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia and hemoconcentration are more prominent in dengue. In chikungunya, hemoconcentration is virtually absent but lymphopenia is more prominent.

The diagnosis of chikungunya is made on the basis of the overall picture and confirmed by detecting the virus, viral RNA or chikungunya virus-specific antibodies. Viral isolation or culture is best done on or before the second day of illness as the antibody response diminishes yield. Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detects viral nucleic acid. Antigen capture ELISA and indirect immunofluorescence are rapid and sensitive ways to document the immune response and may distinguish between IgM (elevated in the first 5 to 7 days of illness) and IgG.

Viral culture, nucleic acid PCR, NS1 antigen and dengue IgM and IgG are all used to document dengue infection. Early indicators also help diagnose the disease such as the tourniquet test and a white cell count <5,000/cu mm. The presence of fever with a positive tourniquet test or leukopenia plus one other clinical feature has a higher positive predictive value than fever with any two features. An elevated AST also helps distinguish dengue from other viral illnesses.

Supportive therapy

Therapy for both diseases is mainly supportive. Because of the joint pain, patients with chikungunya may require treatment with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) both in the acute illness and during subsequent attacks of chronic joint symptoms. Gatchalian, however, warns the clinician about committing to a diagnosis of chikungunya before treating a patient with NSAIDs. “In places where both dengue and chikungunya actually circulate, it is always important to consider dengue before you even give any NSAIDs for chikungunya because NSAIDs can cause you some bleeding,” she explained.

Outcomes and researches

Dengue mortality in the Philippine may reach as high as 50 percent, possibly due to delays in seeking care. In chikungunya, mortality is much lower, and life-threatening complications are very rare, but patients may have chronic arthritis and destructive arthropathy. Cases of encephalitis with residual neurologic deficits have been reported but are rare.

Vaccines development for both diseases is underway, but presently the major preventive measures available focus on vector control. As the mosquito larvae are found in collections of clean water, households must be thoroughly and carefully inspected to preempt vector proliferation.