Genetic study leads to tool to help determine women’s breast cancer risk

Photo Credit: Cancer Research Malaysia

Photo Credit: Cancer Research Malaysia

The tool, known as a polygenic risk score (PRS), stratifies women into risk groups ie, their risk of developing breast cancer, based on their genetic sequence. It is hoped that the tool can empower women to decide on suitable screening and prevention programmes for themselves. This will, in turn, reduce inefficiency, unnecessary cost and possible harm due to overdiagnosis.

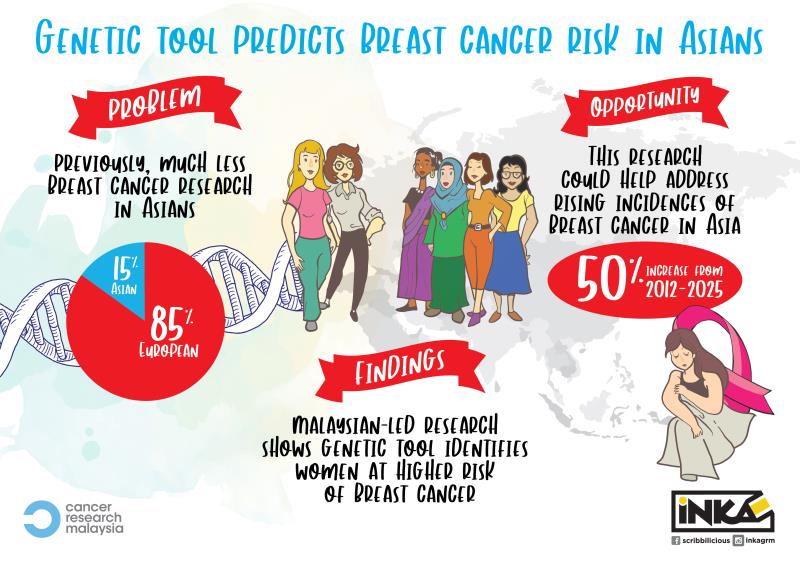

The study, spearheaded by Malaysian scientists in collaboration with colleagues from Singapore and University of Cambridge, UK, is the first large study into the PRS of an Asian population. The PRS tool was previously developed for European women and the current study demonstrated its applicability to Asian women.

According to Professor Datin Paduka Teo Soo-Hwang, OBE, Chief Scientific Officer at Cancer Research Malaysia (CRM) and co-lead of the study, previous Asian studies were nearly six times smaller than studies carried out in European cohorts. Due to the lack of data in Asians, it was unclear if PRSs are effective in predicting breast cancer risk in non-European women. Teo said: “Through the significant increase in data from Malaysia and Singapore, we now know PRS can help us identify more accurately who is at high risk of breast cancer. Our results suggest that only 30 percent of Malaysian and Singaporean women have a predicted risk similar to that of European women, and that using the PRS accurately identifies these high-risk women.”

The multinational study was a collaboration between CRM and Associate Professor Ho Weang Kee, of University of Nottingham; Professor Douglas Easton and Professor Antonis Antoniou, of University of Cambridge, UK; Professor Nur Aishah Mohd Taib, of Universiti Malaya Cancer Research Institute; Professor Dato’ Dr Yip Cheng Har, of Subang Jaya Medical Centre (SJMC); Associate Professor Mikael Hartman, of Singapore National University Health System; Dr Li Jingmei, of Genome Institute of Singapore; and six hospitals in Singapore. It also involved a large population-based prospective cohort from Singapore. The study was published in Nature Communications. [Available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17680-w]

“Combining genetic factors into one comprehensive model is critical to move from the research to a tool for women to use. We evaluated the PRS in 45,212 Asian women from Singapore, Malaysia, Japan, Korea, China, Hong Kong, Thailand, Taiwan, US, and Canada. Studies such as these require large sample sizes, and so, bringing together patients from Universiti Malaya, SJMC, National University Hospital, Singapore, and six other major treatment centres in Singapore really gave us the sample size to be able to evaluate the tool in Asians,” said Ho, the study’s first author.

Antoniou, co-lead of the study, said: “We have been developing a model for predicting breast cancer risk in European women that includes the PRS and this is now approved for clinical use. This study is the first big step towards enabling the use of such tools in the clinical management of women of Asian ancestry.”

Another co-lead of the study, Easton, said the research represents a critical piece of the puzzle that helps to better understand breast cancer risks in different women around the world. He said: “There are differences in the genetic make-up of Asian women compared to women of European descent, which means their propensity to develop breast cancer may be different. Understanding this can help us to work out why some women are at higher risk of the disease, which in turn should help us to improve screening, prevention, and ultimately, treatment of the disease.” Easton is director of the Centre for Cancer Genetic Epidemiology at the University of Cambridge in UK.

Women are generally recommended to start screening for breast cancer at the age of 50. However, in most Asian countries, many women who could be at risk of breast cancer do not go for screening. This leads to late detection and a lower survival rate. “Risk-based screening may be particularly important in low- and middle-resource countries that do not have population-based screening, such as Malaysia. Without the funding for population-based screening, identifying individuals with higher risk may be an important strategy for early detection,” said Nur Aishah.

The PRS tool’s arrival is timely as there is an urgent need to develop an appropriate screening strategy for Asian women, especially Malaysian women. The country anticipates a 49 percent increase in breast cancer cases from 2012 to 2025 and has a much lower 5-year survival rate compared to other Asian countries at only 63 percent, whereas the 5-year survival rate in South Korea and Singapore is 92 percent and 80 percent, respectively.

About the study

The study evaluated the best performing PRSs for European-ancestry women using data from 17,262 breast cancer cases and 17,695 controls of Asian ancestry from 13 case-control studies, and 10,255 Chinese women from a prospective cohort (413 incident breast cancers). It arrived at the conclusion that the “PRS developed for European-ancestry women is also predictive of breast cancer risk in Asian women and can help in developing risk-stratified screening programmes in Asia.”

The study also revealed that, compared to women in the middle quintile of the risk distribution, women in the highest 1 percent of PRS distribution have an estimated 2.7-fold risk and women in the lowest 1 percent of PRS distribution have an estimated 0.4-fold risk of developing breast cancer. Also worthy of note is the fact that there is no evidence of heterogeneity among Malay, Chinese and Indians in terms of PRS performance, making it suitable for use in our country.