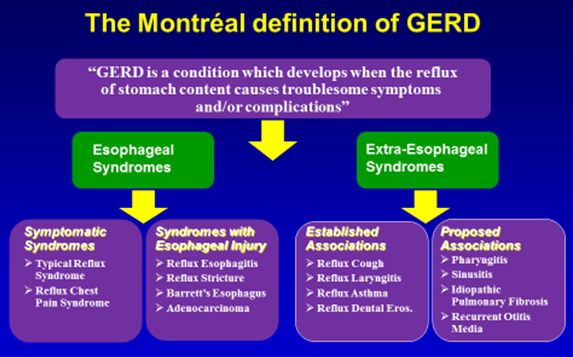

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a condition which develops when reflux of stomach contents causes troublesome symptoms and/or complications.1 Audrey Abella speaks with Dr Tan Chi Chiu, gastroenterologist and senior consultant, Gastroenterology & Medicine International at Gleneagles Medical Centre, Singapore, to discuss how GERD can be addressed in the primary care setting.

Vakil N. J Gastroenterol 2006;101:1900-1920

Vakil N. J Gastroenterol 2006;101:1900-1920Introduction

GERD is a common condition in the general population and is seeing an increasing prevalence in Asia. Studies in Asia based on symptoms and endoscopic oesophagitis have shown a prevalence as high as 25 percent but with wide variability among countries. One possible reason for this rise is increasing obesity.

Two classic symptoms of GERD:

Heartburn - a burning sensation in the midchest, at times rising from the upper abdomen to the chest. It can be severe enough to be painful. Often, it occurs after eating or when lying down.

Acid reflux - stomach fluids reflux into the throat or mouth, with a sour or bitter taste.

At times, the acidic fluid overflows into the larynx and airways, causing reflux cough, pharyngitis, or even asthmatic symptoms. These constitute “extra-oesophageal reflux disease”. Although less common, the prevalence is also rising in tandem with GERD.

Patients with GERD may also complain of the following symptoms:

• Belching

• Chronic sore throat

• Difficulty or pain when swallowing

• Waterbrash

• Hoarseness

• Sour taste in the mouth

• Halitosis

• Gingivitis

• Tooth enamel erosion

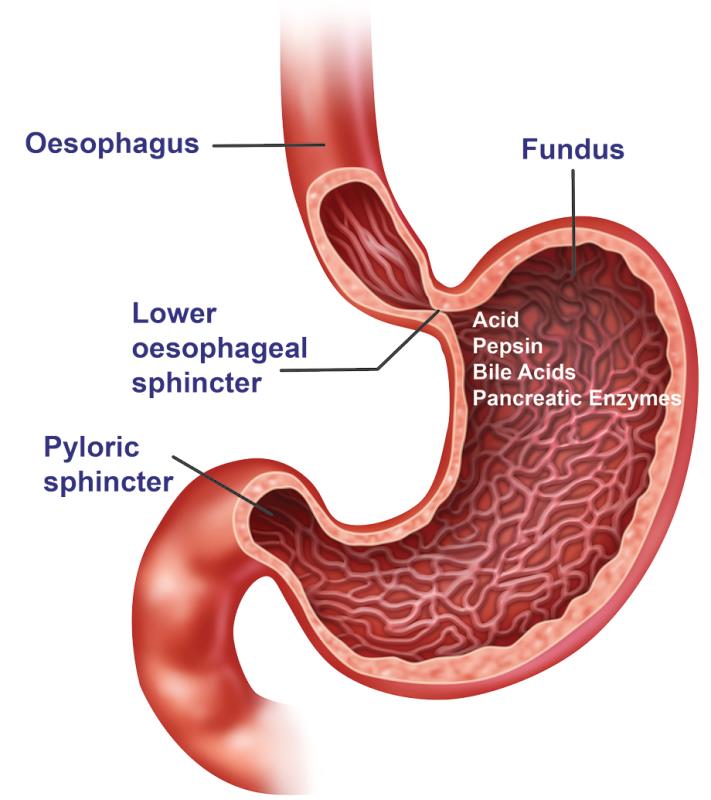

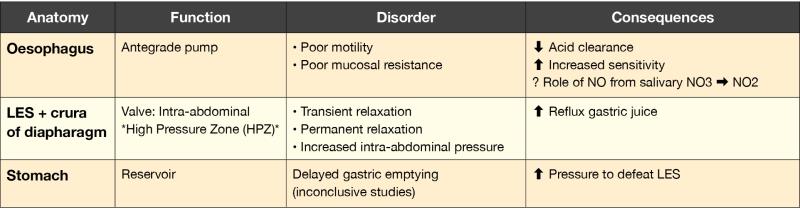

Normally, there is a muscular valve at the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ). Whether the valve is too weak (sometimes in association with hiatal hernia, thus allowing more acid to rise), or the lining of the oesophagus is too sensitive, or a combination of both, acid causes inflammation, hence the heartburn.

Pathogenesis of GERD

Risk factors for the development of GERD include older age, male gender, race (Indian), family history, higher socio-economic status, and certain medications (eg, B-agonists, nitrates, Ca blockers, anticholinergics, progesterone, nicotine).

There is conflicting evidence regarding other factors. Lifestyle factors are not the dominant factor in the pathogenesis of reflux oesophagitis; modifications are not shown to be effective and are not recommended as primary treatment for GERD.

However, weight loss in obese individuals has been shown to improve GERD. Evidence is less convincing for smoking, alcohol, caffeine, diet, and psychological factors.

Is GERD dangerous?

Acid that refluxes into the oesophagus can sometimes cause much inflammation, damage, and scarring. Most often though, the acid only causes symptoms with either minimal or no visible inflammation. This is classified as nonerosive reflux disease (NERD).

Dangers of acid reflux damage:

a. Erosions or shallow ulcers at the lower end of the oesophagus. If deep enough, these could burrow into blood vessels and cause bleeding.

b. Severe damage may cause scarring and narrowing (stricture), making swallowing difficult, with food becoming stuck on the way down (dysphagia) with pain or discomfort (odynophagia).

c. The lining of the lower oesophagus might be scarred enough to alter the cells to a type called Barrett’s oesophagus. This is seen endoscopically as a projection of red columnar epithelium above the squamous-columnar junction, at least 1 cm. Long-segment Barrett’s (>3 cm) is considered a risk factor for progression into oesophageal adenocarcinoma. However, in Asia, the prevalence of Barrett’s oesophagus is lower than in the west. Risk factors in Asia-Pacific are ethnicity (more in Caucasians and Indians), older age, male gender, long duration of reflux symptoms, abdominal obesity, and smoking. It is controversial whether a histologic finding of intestinal metaplasia is an essential criterion for diagnosis.

There is little correlation between the severity of heartburn and the damage in the oesophagus. Some may have terrible heartburn but slightly visible inflammation (ie, NERD), while others may have minor symptoms but with badly scarred oesophagus. Therefore, the actual severity of symptoms is not very helpful.

However, symptoms that could be considered alarming are extreme pain, difficulty or painful swallowing, regurgitating or vomiting blood, loss of weight, loss of appetite, or anaemia. In such cases, there is a higher suspicion of possible serious consequences of acid reflux as described above.

Diagnosing GERD

Apart from good history taking and a comprehensive clinical examination, gastroscopy – the “gold standard” for diagnosing erosive oesophagitis – could be offered to:

• Identify mucosal involvement (including erosions, ulcerations, strictures, Barrett’s oesophagus, and oesophageal cancer)

• Exclude other upper gastrointestinal pathology (eg, peptic ulcer, gastric cancer)

• Allow diagnosis (biopsy) or therapy (dilation, etc) for complications

• Exclude rarer causes of oesophageal symptoms (eg, viral oesophagitis, eosinophilic oesophagitis, candidiasis) Biopsies may be taken when the degree of damage is visible. If there is oesophagitis, it can be classified into Los Angeles grades A–D depending on severity. If there is no visible inflammation but symptoms are typical, it could be NERD. For further confirmation of acid reflux, tests such as oesophageal pH monitoring or manometry, or pH-impedance monitoring (detecting fluid shifts in the oesophagus) may be offered.

Treating GERD

Treatment objectives:

1. Relieve symptoms

2. Heal oesophagitis

3. Restore quality of life

4. Prevent relapse of symptoms

5. Prevent complications

The most commonly used medicines are those that neutralize stomach acids (antacids) or reduce acid production (including H2-receptor blockers, but more typically proton pump inhibitors [PPIs]) depending on the degree of symptoms and severity of the oesophagitis. Generally, patients are given a course of medication, gradually tapering to the smallest dose that can keep patients symptom free. For NERD, patients can be taken off medicine or instructed to take only “on demand” (ie, when symptoms occur) and stop when they are relieved. Some patients need continuous maintenance medicine to stay well and prevent recurrence of erosions. The worse the oesophageal erosions are, the more likely maintenance therapy is needed.

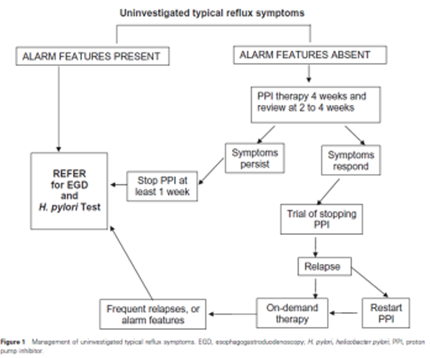

Can GERD be treated without first undergoing any tests?

The answer somewhat varies depending on the availability and cost of testing modalities. For mild symptoms, a GP might offer a trial of empirical treatment with medicine to reduce acid production in the stomach. These can range from antacids to H2-receptor blockers to PPIs. If effective in providing relief, patients should be monitored to check for recurrence. If these do recur or worsen, or some alarm symptoms appear, it would not be reasonable to continue empirical treatment. Patients should then undergo further tests by a gastroenterologist.

However, if symptoms are significant and specialist care is readily available, it may be advantageous to refer patients for gastroscopy first to determine whether there is erosive oesophagitis. If gastroscopy is done after a period of PPI use, even if there were erosions at the beginning, these might have been “papered over” by PPIs, wrongly classifying cases as NERD, with therapeutic and prognostic implications.

Algorithm for noninvestigated GERD in Asia

Fock KM. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;23:8-22

Fock KM. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;23:8-22

Managing complications

a. If there is oesophageal narrowing due to scarring – hydrostatic (water filled) balloon dilators passed through gastroscopes or bougies (ie, solid dilating devices passed through under X-ray fluoroscopy guidance) can stretch the narrowed part, with minor risk of bleeding and perforation.

b. If there is evidence of Barrett’s oesophagus – continued use of a PPI may reduce the risk of progression to cancer; however, evidence is inconsistent. Surveillance by gastroscopy and biopsy may be undertaken to see whether there is any progression towards cancer. Whether such surveillance should be done in Asia (and if so, what is the best interval) and whether advanced endoscopic examination techniques ought to be employed remain controversial. The benefits of such surveillance should be discussed with individual patients with their specific risk factors to decide the best course of action.

Refractory GERD

This is a type of GERD that does not respond satisfactorily to standard PPI doses for at least 8 weeks. This seems to be more prevalent in patients with NERD, with various possible causes.

Reflux-related causes are ongoing acidic and nonacidic reflux (eg, pepsin and bile reflux). Nonreflux causes include dysmotility, eosinophilic oesophagitis, functional heartburn, overlap syndrome with irritable bowel syndrome, and visceral hypersensitivity. Nonreflux causes may be due to impaired response to PPIs, which may be tied to several factors including increased body weight or genotypes of the P450 system that influence PPI metabolism.

In general, patients with refractory GERD require further investigation (ie, gastroscopy if not already done, and pH-impedance and manometry tests). If acid is the presumed cause, options include changing PPIs, switching to a potassium channel blocker, or adding H2-receptor blockers or even alginate antacids on top of PPIs to improve control.

In worst cases, or cases that respond poorly to medicine, fundoplication surgery to tighten the valve at the GEJ may be offered. This is a highly specialized surgery offered only for the most difficult cases. This should only be considered after confirming by pH-impedance and manometry tests that reflux is indeed the cause of symptoms. Surgical outcomes can be very good in centres with much experience. Newer plication methods using special endoscopes are under development.

What about lifestyle?

A few lifestyle changes may be helpful. Weight reduction has been shown to be effective in reducing reflux symptoms often in association with standard reflux treatment. Even a 10-percent drop in weight has been shown to improve symptoms. Bed elevation has also been shown to be helpful (ie, the head of the bed can be elevated by about 20 cm). It is important to note that the whole bed must be on a slight incline. High pillows that merely raise the head but not the trunk do not work.

Other methods with less conclusive evidence include refraining from eating large meals, or near bedtime; not lying down for at least 3 hours after meals; and avoiding smoking and alcohol. While there is no standard list of foods to avoid, specific foods than can be bothersome should be avoided.

Conclusion

GERD is becoming more common in Asia. Heartburn and acid reflux are the two classic symptoms which may be sufficient to lead to a clinical diagnosis. Investigative methods start with gastroscopy and could, in some cases, include pH monitoring, manometry, and pH-impedance monitoring.

Given the therapeutic and prognostic implications in differentiating between NERD and erosive reflux oesophagitis, as well as excluding other diagnoses that may have overlap symptoms, if resources are available and affordable, conducting gastroscopy before definitive PPI treatment offers some advantage. However, in milder cases, empirical treatment can be started. If symptoms recur or worsen, or alarm features appear, referral to specialist care would be recommended.

The mainstay of treatment is PPIs. Refractory cases should be further evaluated to determine the cause. Patients with proven refractory reflux may benefit from fundoplication surgery in centres with much experience. Complications to be prevented include bleeding, strictures, Barrett’s oesophagus, and oesophageal adenocarcinoma.