Atezolizumab + chemo gets greenlight from HSA for PD-L1+ TNBC

Atezolizumab, in combination with the chemotherapy nab-paclitaxel, has been approved by the Singapore Health Sciences Authority (HSA) for the first-line treatment of unresectable locally advanced or metastatic, PD-L1-positive (PD-L1+) triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) — adding to the growing market list this drug has been granted approval for TNBC.

Atezolizumab, a PD-L1 inhibitor, represents the first immunotherapy approved for TNBC, based on findings from the IMpassion130 trial.

Among patients with PD-L1+ status, adding atezolizumab to nab-paclitaxel significantly extended progression-free survival (PFS) by 2.5 months compared with nab-paclitaxel alone (median, 7.5 vs 5.0 months) — with a 38 percent reduction in the risk of disease progression or death (hazard ratio [HR], 0.62; p<0.001). [N Engl J Med 2018;379:2108-2121]

Overall survival (OS) was also longer by 7 months with the addition of atezolizumab vs chemotherapy alone in this patient subgroup (median, 25.0 vs 18.0 months; HR, 0.71, 95 percent confidence interval [CI], 0.54–0.94) in the second interim analysis. [Lancet Oncol 2020;21:44-59]

During the ESMO 2018 Congress, when the first interim results were presented, lead investigator Professor Peter Schmid of Barts Cancer Institute in London, UK, hailed atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel as “a new standard of care” for patients with PD-L1+ status, adding that the findings “will change the way TNBC is treated”.

Dr Karmen Wong, a medical oncologist from Icon Cancer Centre Singapore, Singapore, who is unaffiliated with the study, echoed the same enthusiasm. She said the combination regimen presents a new standard of care — in view of the greater number of patients who responded and lived longer with atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel compared with chemotherapy alone in the study.

“Atezolizumab in combination with nab-paclitaxel is the first targeted treatment to improve survival in metastatic TNBC [mTNBC],” Schmid said. “It is also the first immunotherapy to improve outcome in this cancer. Most of the survival benefit was in patients with PD-L1+ tumours.”

Prior treatment landscape

TNBC constitutes 15–20 percent of breast cancer cases, and implies a fairly aggressive form of cancer, according to Wong. Prognosis for TNBC is poor in comparison to other breast cancer subtypes: the median survival was 12–15 months once the disease becomes metastatic, compared with an average of 3–4 years survival for a receptor-positive breast cancer.

The poor prognosis of TNBC is not because it is more aggressive than the other breast cancer subtypes, but rather, there are better treatment options available for receptor-positive breast cancer, she pointed out.

“What TNBC means is that the conventional signals seen on breast cancer — ie, oestrogen and progesterone receptors — are absent. As a result, targeting the disease using an endocrine therapy is not feasible,” explained Wong.

“Likewise, the HER2 signal which is driving breast cancer growth is also absent. Consequently, targeted therapy using anti-HER2 antibody is not effective. So what is left is the option of chemotherapy,” she continued.

Conventionally, TNBC is treated with systemic chemotherapy. According to Wong, the most commonly used chemotherapy is taxane-based such as paclitaxel or docetaxel. Often, a taxane-based chemotherapy is combined with platinum-based therapy such as carboplatin or cisplatin.

However, most patients eventually develop resistance within a few months.

“The unmet need in managing mTNBC is, therefore, not that the response rate is poor, but the response is usually short,” said Wong. “By 2 years, most patients may have died from the disease. Control of the disease is simply not optimal at the moment.”

IMpassion130: Clinically meaningful benefits

The multinational, phase III, double-blind trial involved 902 patients with metastatic or inoperable locally advanced TNBC who had not previously received chemotherapy for metastatic disease.

They were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive either intravenous atezolizumab 840 mg (median age 55 years) or placebo (median age 56 years), both in addition to a chemotherapy backbone of intravenous nab-paclitaxel 100 mg/m2. Atezolizumab was given on days 1 and 15 whereas nab-paclitaxel was given on days 1, 8, and 15 of a 28-day cycle until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

The study met its coprimary endpoint of PFS, both in the intention-to-treat population and in the PD-L1–positive subgroup. In the first interim analysis, the addition of atezolizumab significantly extended PFS compared with nab-paclitaxel alone in the intention-to-treat population (median, 7.2 vs 5.5 months; HR, 0.80; p=0.002) over a median follow-up of 12.9 months. The relative PFS benefit was even more pronounced in patients with PD-L1+ disease, with a risk reduction of 38 percent in favour of atezolizumab (median, 7.5 vs 5.0 months; HR, 0.62; p<0.001).

In the second interim analysis, OS data was considered mature after a median follow-up of 18.0 months covering an information fraction of 80 percent.

Median OS in the intention-to-treat population was 21.0 months in the atezolizumab arm compared with 18.7 months in the chemotherapy alone arm (HR, 0.86; p=0.078). Among patients with PD-L1+ status, median OS was longer by 7 months with atezolizumab vs chemotherapy alone (median, 25.0 vs 18.0 months; HR 0.71, 95 percent CI, 0.54–0.94).

“The findings of this second interim OS analysis, reported here, provide evidence that the clinical benefit is consistent and maintained with extended follow-up,” stated the investigators.

Although the statistical significance was not formally tested due to the prespecified statistical testing hierarchy — whereby testing of the PD-L1+ subgroup comes after and only if the between-group difference in the intention-to-treat population reached significance — the investigators deemed the survival benefit “clinically meaningful in the PD-L1+ population”, with a difference of 7 months between treatment groups.

Consistent with the primary analysis, the updated data on PFS in the second interim analysis showed a significant benefit with the addition of atezolizumab over chemotherapy alone. Median PFS was 7.2 vs 5.5 months for atezolizumab vs chemotherapy alone, respectively, in the intention-to-treat population (HR, 0.80; p=0.0021); while the corresponding median PFS was 7.5 vs 5.3 months, respectively in the PD-L1+ subgroup (HR, 0.63; p<0.0001).

“Since no treatment [benefit] was seen in the PD-L1-negative subgroup, the clinical benefit of atezolizumab in the intention-to-treat population was driven by the improvement in PFS in the PD-L1+ subgroup,” observed the investigators.

PD-L1+ status was defined as ≥1 percent PD-L1 expression on tumour-infiltrating immune cells, which in the study, was evaluated using the SP142 PD-L1 immunohistochemical assay.

“Approvals by US and European Union regulatory agencies, and the inclusion of this regimen in US National Comprehensive Cancer Network treatment guidelines, highlight that atezolizumab plus nab-paclitaxel could be a new standard of care for previously untreated patients with PD-L1 immune cell-positive, unresectable, locally advanced or mTNBC,” the investigators added.

“The take-home message from the study is that this combination regimen does provide an improved outcome in patients with mTNBC in the first-line setting,” Wong summed up. “Although there are improvements, there are still other areas to address, for instance, the optimal chemotherapy backbone to use in combination with anti-PD-L1.”

Safety profile

There were no new adverse effects (AEs) identified with the combination therapy — the safety profile was consistent with the individual drugs.

Up till the cutoff date for the second interim analysis, grade 3 or 4 AEs occurred in 49 percent of patients treated with atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel compared with 43 percent of patients receiving chemotherapy alone. The most common grade 3–4 AEs were neutropenia (8 percent vs 8 percent), peripheral neuropathy (6 percent vs 3 percent), decreased neutrophil count (5 percent vs 4 percent), and fatigue (4 percent vs 3 percent).

There were two treatment-related deaths in the atezolizumab group and one in the chemotherapy alone group during the study. Among the atezolizumab-treated patients, one died of autoimmune hepatitis related to atezolizumab and another was due to septic shock related to nab-paclitaxel. In the chemotherapy alone group, the death was due to hepatic failure.

Based on personal clinical experience, Wong observed that rash is the most common AE associated with atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel, occurring in 15–20 percent of her patients. Other commonly seen AEs in her practice include endocrine problem (8 percent), thyroiditis, diabetes, and fever.

“Doctors need to be able to recognize the side effects and know how to manage them promptly,” said Wong. “Some of the signs can be nonspecific, so you need to gain experience to be able to recognize them.”

Challenges in workup for TNBC

“Often, you need to validate if the tumour is truly triple negative,” said Wong. A receptor-positive breast cancer may be wrongly diagnosed as TNBC due to false negative results in the staining test for the triple receptors.

“In TNBC, you will also want to find out if they are actually a BRCA mutation carrier. If so, targeted treatments are available.”

For stage 4 breast cancer, guidelines recommend genetic testing to guide targeted therapy, Wong noted. Other tests that oncologists can offer include immunoscore and tumour genomic testing to inform treatment decision.

The main factors to consider when deciding whether to undergo a test include the availability and affordability of treatment. “There is no point to undergo a test if the patient can't afford the immunotherapy treatment,” said Wong.

Importance of PD-L1 testing: Pathologist perspective

Based on the study, only patients tested positive for PD-L1 are likely to benefit from atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel. Therefore, it is important that patients with mTNBC undergo PD-L1 testing using SP142 assay.

“The IMpassion130 is a landmark study — this is the first time a study shows that the PD-L1 SP142 biomarker is an indicator for improved survival and response duration [with an immunotherapy] in patients with mTNBC,” said Dr Brendan Pang, a consultant pathologist at ParkwayHealth Laboratory, Singapore, who is unrelated to the study.

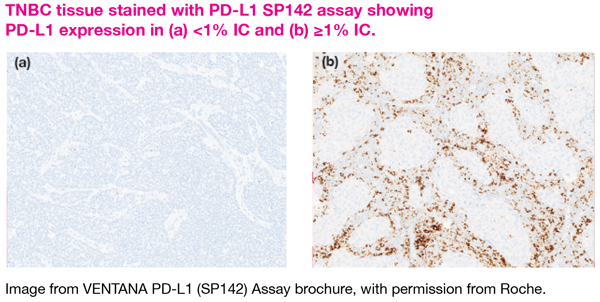

Unlike PD-L1 testing on other types of cancer like NSCLC whereby PD-L1 can be scored on the tumour cells, PD-L1 staining was done on the tumour-infiltrating immune cells (IC) for TNBC.

“This is because the expression of PD-L1 on tumour cells of TNBC is very low. In TNBC, PD-L1 tends to be expressed on IC rather than on tumour cells,” Pang explained. “Also, the SP142 assay antibody is more sensitive to and binds preferentially to PD-L1 on IC rather than the tumour cells.”

For TNBC, determination of PD-L1 status on the SP142 assay is based on the percentage of tumour area occupied by the IC that express PD-L1. A PD-L1 expression level of ≥1 percent on the IC is considered to be positive for PD-L1.

In addition, prompt fixation of sample is crucial to preserve the antigen for recognition by the assay antibody, he added. As such, getting an accredited laboratory for PD-L1 testing is the key.

“Also, it is important to note that each drug will need its own assay,” Pang pointed out. “Do not interchange the antibody for PD-L1 SP142 staining from other assays — different clones of antibody might have differential sensitivity to PD-L1.”

In light of the nonconcordance of the PD-L1 SP142 assay with the other tests for PD-L1, the different assays for PD-L1 cannot be considered as equivalent. [SABCS 2019, abstract PD1-07; ESMO 2019, abstract LBA20]*

“Routine testing for PD-L1 immune-cell expression in unresectable, locally advanced, or mTNBC with the [FDA-]approved companion diagnostic PD-L1 SP142 assay should be used to identify patients who might benefit from treatment with atezolizumab plus nab-paclitaxel,” highlighted the investigators of IMpassion130.

To encourage uptake of the testing, there is a patient support programme from the manufacturer of SP142 assay (Roche) that covers the testing cost for PD-L1 using the assay, beginning in August 2020. In addition, increasing the awareness of the assay and the subsidy programme among oncologists may help, suggests Pang.