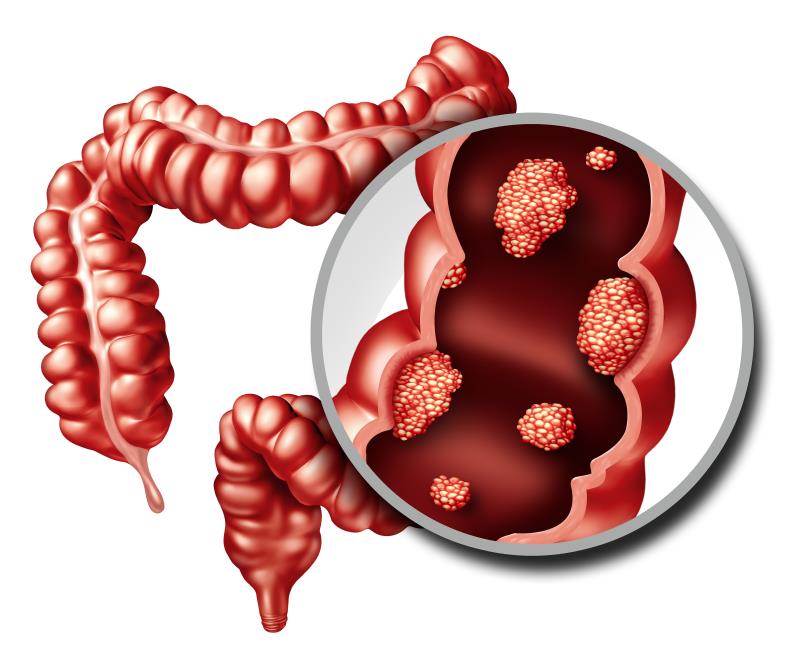

The plant alkaloid berberine effectively reduces the risk of recurrent colorectal adenoma in individuals who had recently undergone polypectomy, according to a study — thus providing a potential option for chemoprevention of adenoma.

Significantly fewer participants receiving berberine had recurrent colorectal adenomas, any polypoid lesions, or advanced colorectal adenomas compared with those on placebo over 2 years of follow-up.

“Although screening for colorectal cancer [CRC] and precancerous adenomatous polyps (adenomas) has been successful in reducing CRC mortality, there are barriers to widespread implementation … Thus, novel strategies for prevention remain an important unmet need,” wrote Drs Kwon Sohee and Andrew Chan of Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, US in a commentary. [Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 5:231-233]

“Chemoprevention, defined as the use of agents (eg, medications, vitamins, or supplements) for the inhibition, delay, or reversal of carcinogenesis, is an appealing alternative or complement to screening, particularly in resource-limited settings,” they added.

In the double-blind, multicentre trial, 1,108 individuals aged 18–75 years (≥75 percent ≥50 years, 35 percent female) who had undergone complete polypectomy within the past 6 months with 1–6 histologically confirmed colorectal adenomas were randomized 1:1 to receive berberine 0.3 g twice daily or placebo. [Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 5:267-275]

The primary outcome of recurrent adenoma was detected in significantly fewer participants in the berberine group than the placebo group during a median follow-up of 25.5 months (36 percent vs 47 percent; relative risk ratio [RR], 0.77; p=0.001).

The results remained consistent even after adjusting for advanced colorectal adenoma at baseline—which portends a higher risk for recurrence of adenoma (adjusted RR, 0.78; p=0.002), as well as in per-protocol analysis (RR, 0.78; p=0.002).

Similarly, berberine led to significantly lower rate of advanced colorectal adenomas (3 percent vs 6 percent; odds ratio [OR], 0.52; p=0.05) and any polypoid lesions (43 percent vs 55 percent; RR, 0.77; p=0.0002) during follow-up compared with placebo.

There were no cases of CRC reported during the follow-up period. Adverse events (AEs) occurred rarely and no serious AEs were reported, which according to the authors, indicate that is safe and may present as a promising agent for chemoprevention after polypectomy.

Although constipation occurred more commonly in the berberine than the placebo groups (1 percent vs <0.5 percent; p=0.11), the difference was not significant between groups and were mostly relieved within a week after using a prokinetic drug.

Agent with an ancient past

Touting berberine as an agent with an ancient past, Kwon and Chan noted that the isoquinoline quaternary alkaloid extracted from medicinal plants has widely been used in Ayurvedic and Chinese medicine for centuries to cure diarrhoea and enteritis.

Preclinical studies in animals have suggested that berberine changed the composition of the gut microbiota and inhibit signalling pathways leading to tumorigenesis.

“[This] trial is the first evidence … in human beings, validating the significant body of experimental data and offering compelling proof-of-principle of the potential value of repurposing a natural product for chemoprevention,” stated Kwon and Chan.

Nonetheless, they could not recommend the use of berberine for CRC prevention yet due to several limitations. Lack of a standardized surveillance protocol for recurrent polyps in the study means that the number and time interval for follow-up colonoscopies could vary among the participants, leading to confounded results. The extremely low AE rate in the placebo group, with only one constipation case reported, might indicate underreporting of AEs.

“However, the promising results of Chen and colleagues warrant follow-up through additional, larger randomized trials, including in non-Asian populations,” they suggested.