At the recent collaborative online forum titled ‘Navigating Medication Safety during COVID-19’ organized by the Asian Young Pharmacist Group (AYPG) and MIMS, representatives of five Asian countries shared their local experiences and current protocols for pharmacotherapy in treating patients with COVID-19. Here, we present an edited version of their comments.

Malaysia

Teoh Cherh Yun, clinical pharmacist, Hospital Sultanah Maliha, Langkawi

In Malaysian, as of Day 22 of the national Movement Control Order (MCO), a total of 4,119 cases of COVID-19 have been confirmed by the Ministry of Health (MOH). There have been intense outbreaks in certain areas such as stratified buildings and apartments, leading to the government declaring enhanced MCOs there to control the movements of residents and intensify screening.

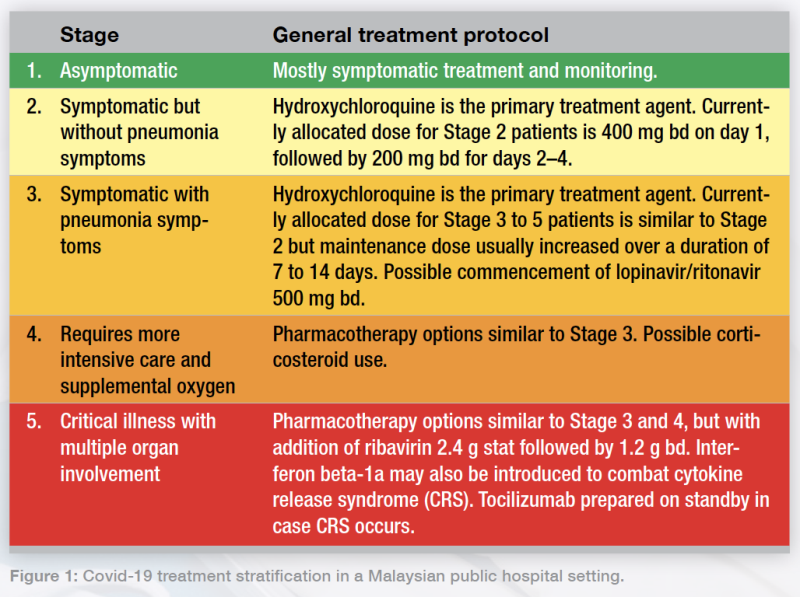

I’m part of the COVID-19 management team in a government hospital under the MOH. Here, we stratify confirmed cases in five clinical stages.

Figure 1: Covid-19 treatment stratification in a Malaysian public hospital setting.

Figure 1: Covid-19 treatment stratification in a Malaysian public hospital setting.The first wave of patients with COVID-19 in Malaysia were mostly Stage 1 and 2 cases consisting mostly of inbound travellers from other countries. In the second wave, which saw an exponential increase coming from mass gatherings, more patients required ventilation and ICU care.

To our best knowledge, there are conflicting opinions on hydroxychloroquine dosing. Some papers suggested 200 tds, but here we use a 400 bd loading dose on day 1 followed by 200 bd on subsequent days. If the patient has severe renal impairment—indicated by a creatinine clearance <30 mL/min/1.73m2—we half the dosage, based on local consensus with our infectious disease (ID) physician. This may differ among centres and physicians.

For Stage 3 and 4 patients, we use hydroxychloroquine and lopinavir/ritonavir as these agents have good potential. Hydroxychloroquine, besides being an immunomodulator, may also prevent the lysosomal and endolysosomal actions of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, stopping it from viral fusion with host cells itself. Corticosteroids are used mainly for severe (stage 4 and 5) cases.

I’m currently handling a Stage 5 patient in the ICU in my hospital; we’re learning [about the best options] as we go along. We’re trying ribavirin and starting to use interferon to prevent cytokine release syndrome (CRS). In my centre, we also prepare tocilizumab as a contingency CRS treatment. Other than those, we’re giving them hydroxychloroquine and lopinavir/ritonavir, along with interferon beta-1a 44 mg at TIW dosing, to some good effect.

To evaluate the patients’ risk of CRS, we monitor their ferritin levels, cytopenia signs, and HScore. We also monitor creatinine levels and other parameters to ensure that there aren’t any inflammatory sequelae; if there are, there is greater risk of CRS and mortality from COVID-19.

We’re also proud to say we’re one of the Asian countries selected to enrol into the WHO Solidarity trial. Nine MOH hospitals have been selected as trial centres, with Dr Chow Ting Soo, infectious disease physician, Penang Hospital, leading the Malaysian trials.

Recently, we have also started testing convalescent plasma treatment. Patient 46 in our MOH database, who recovered and was discharged, has offered himself as a plasma donor. We’re yet to see if it would be a helpful addition in our local setting to curb COVID-19.

Indonesia

Yulia Nur Ulfa, head pharmacist, Citra Arafiq Hospital

In Indonesia, we’ve recorded 2,956 cases of COVID-19 up to 8 April. Of these, 204 cases have recovered. The largest areas affected are Jakarta itself as well as much of Central Java.

In my hospital, we have been following guidelines from Indonesian medical institutes regarding pharmacotherapy to treat patients. My hospital is not actually one of those designated to treat COVID-19; there are designated hospitals in various districts.

In general, we treat patients with vitamin C 400 mg, chloroquine, oseltamivir, as well as antibiotics such as azithromycin, ofloxacin, and other quinolones. We also apply nonpharmacological therapies such as hydration and dietary support.

In Indonesia, there have been reported side effects of chloroquine use for treatment of patients with COVID-19, such as tremors, dyspnoea, nausea and vomiting, as well as dizziness. Switching to hydroxychloroquine might reduce the side effects such as vomiting, but I’m only aware of this based on reports from other centres. We have not yet attempted convalescent plasma use.

Japan

Eri Makise, Japan Young Pharmacists Group (JYPG) representative

Until March, the number of confirmed cases in Japan was very low. Since the announcement of the postponement of Tokyo Olympics on 24 March, the official number has unfortunately increased exponentially. As of 8 April, we have 4,354 total cases of COVID-19 and 98 related deaths.

On 7 April, the Prime Minister declared a state of emergency that will last till 6 May. However, this declaration has no legal enforcement in Japan; there is no penalty for citizens who don’t practise social distancing, and no restrictions such as transport shutdowns. Today, many students still go to school and many people still take crowded trains.

In terms of treatment efforts by government and medical institutions, the government expects favipiravir to be effective. Favipiravir, developed by a Japanese manufacturer, has already been tested in more than 120 patients with confirmed improvement. The Japanese government plans to possibly provide it free of charge to up to 50 countries worldwide, with 20 countries already confirmed.

The government has also decided to manufacture enough favipiravir to treat 2 million Japanese citizens by March 2021. However, favipiravir cannot be used for pregnant women due to its teratogenicity.

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are starting in Japan for three other agents. Earlier this March, a German group announced that camostat, a treatment for chronic pancreatic disease, was effective in treating SARS-CoV-2. For this reason, clinical trials with camostat are underway.

The University of Tokyo Graduate School is also starting clinical trials with nafamostat, a drug for acute pancreatic disease, which they expect will block SARS-CoV-2 viral activity at less than 10% of the concentration of camostat.

The third agent, ciclesonide, is an inhaled steroid asthma treatment reported to be effective in three COVID-19 patients at a Japanese hospital, which is now starting clinical trials.

Japan will also participate in an international clinical trial of remdesivir, in a collaboration between the Japanese National Center for Global Health and Medicine (NCGM) and the US National Institutes of Health (NIH).

With these many efforts, we are working to combat COVID-19. I sincerely hope that the impact of COVID-19 will be removed from all over the world.

Taiwan

Henry Ho, hospital pharmacist, National Taiwan University Hospital

Since we lack solid data on the effectiveness and safety profiles of possible pharmacological treatments for COVID-19, supportive care is still our gold standard for managing patients in Taiwan. Only selected patients will undergo trials for antiviral medications.

The regimen used in our hospitals is based on previous in vitro and in vivo studies, observational studies, and clinical trials done not only on SARS-CoV-2 but SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, especially drugs with RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) inhibition mechanisms, due to similarities in RdRp structure among different coronaviruses.

In our considerations for a proper regimen, we use data about the drug concentration needed to reach EC50 (half maximal effective concentration) of the virus, and the drug concentration that can be reached with doses of other indications.

In Taiwan, we have experience in using remdesivir, hydroxychloroquine with or without azithromycin, and interferon beta-1b combined with lopinavir/ritonavir with or without ribavirin.

To safely initiate drugs in patients with COVID-19, side effects, drug-drug interactions (DDIs) as well as complications due to the disease itself must be considered. Patients with COVID-19 are reported to be susceptible to severe complications including cardiac arrhythmia, acute cardiac injury, and shock, especially those who already have underlying cardiovascular disease (CVD).

For example, the hydroxychloroquine-azithromycin combination treatment may potentially have additive QT prolongation side effects. Thus, we monitor ECG readings before and after the initiation of such regimens in order to determine when to discontinue or lower the dose of such regimens in those with higher risk of developing arrhythmia, using a monitoring protocol published by the American College of Cardiology.

Based on previous epidemiological studies, patients with comorbidities such as CVD, hypertension, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and chronic lung disease are at higher risk of developing more severe disease when infected with COVID-19. Thus, plausible DDIs between medications used to treat COVID-19 and those controlling underlying disease cannot be ignored.

Several possible DDIs were documented and were compiled by Liverpool University. Lopinavir/ritonavir may increase bleeding risk while concurrently used with anticoagulants, especially novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs). Hydroxychloroquine may also interact with several antibiotics often used as prophylaxes against bacterial superinfection.

To sum up, possible pharmacological treatments will only be used in selected patients. We’re being extra cautious about potential DDIs and possible drug toxicity related to their use.

Hong Kong

Edward Yau, honorary secretary, Pharmaceutical Society of Hong Kong Student Chapter

In Hong Kong, patients with COVID-19 with mild fever, cough, and no hypoxia are mainly given supportive treatments such as antipyretics and have their vital signs and organ functions monitored. Antiviral drugs may be prescribed by clinicians when patients have respiratory symptoms on hospital admission, or lung radiographs show signs of pneumonia and/or mild hypoxia.

Supportive treatment can be antibiotics, oxygen, or IV fluids. High-flow nasal oxygen (HFNO) or non-invasive ventilation (NIV) are used only in patients showing hypoxaemia or respiratory failure. We liaise with the ICU early if clinical deterioration is anticipated.

Inotropic support with or without steroids are used for cases with septic shock, while mechanical ventilation with or without extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) are used in instances of respiratory failure.

We do not routinely give systemic corticosteroids. At the physician’s discretion, there may be use of short-period, stress-dose steroids (eg, hydrocortisone 200 mg max daily) for refractory septic shock or other clinical indications.

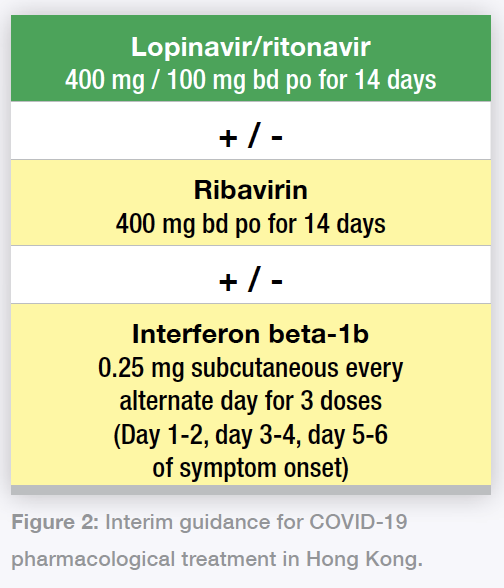

For critically ill patients showing respiratory symptoms, pneumonia and/or hypoxia, the main antiviral drugs used are protease inhibitors lopinavir/ritonavir, ribavirin, and interferon.

Right now, there is still no approved drug indicated for COVID-19 treatment and no current evidence from RCTs to recommend any specific anti-COVID-19 treatment for patients with confirmed infection.

The interim guidance in absence of appropriate clinical trials (Figure 2) is for lopinavir/ritonavir as the backbone therapy, with decisions made based on clinical judgement for ribavirin. Interferon is also being used for some early hospital admissions. These are at the discretion of the hospital or cluster infectious disease (ID) physician in charge.

Figure 2: Interim guidance for COVID-19 pharmacological treatment in Hong Kong.

Figure 2: Interim guidance for COVID-19 pharmacological treatment in Hong Kong.For interferon, we omit remaining doses when COVID-19 symptom onset is beyond 7 days; eg, if patient presents on day 6 of symptom onset, only one dose of interferon should be given; if patient presents with symptoms beyond 7 days, only ribavirin and lopinavir/ritonavir should be given.

Remdesivir was also recently introduced; Hong Kong has joined an international clinical trial for remdesivir in COVID-19 treatment. We’re still waiting for more information and data on this drug as it comes out. Overall, clinicians are encouraged to join any available clinical trials, as they can provide valuable data not only for ourselves but for the rest of the world.